This post may include affiliate links, which means we make a small commission on any sales. This commission helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thanks for supporting small, independent media!

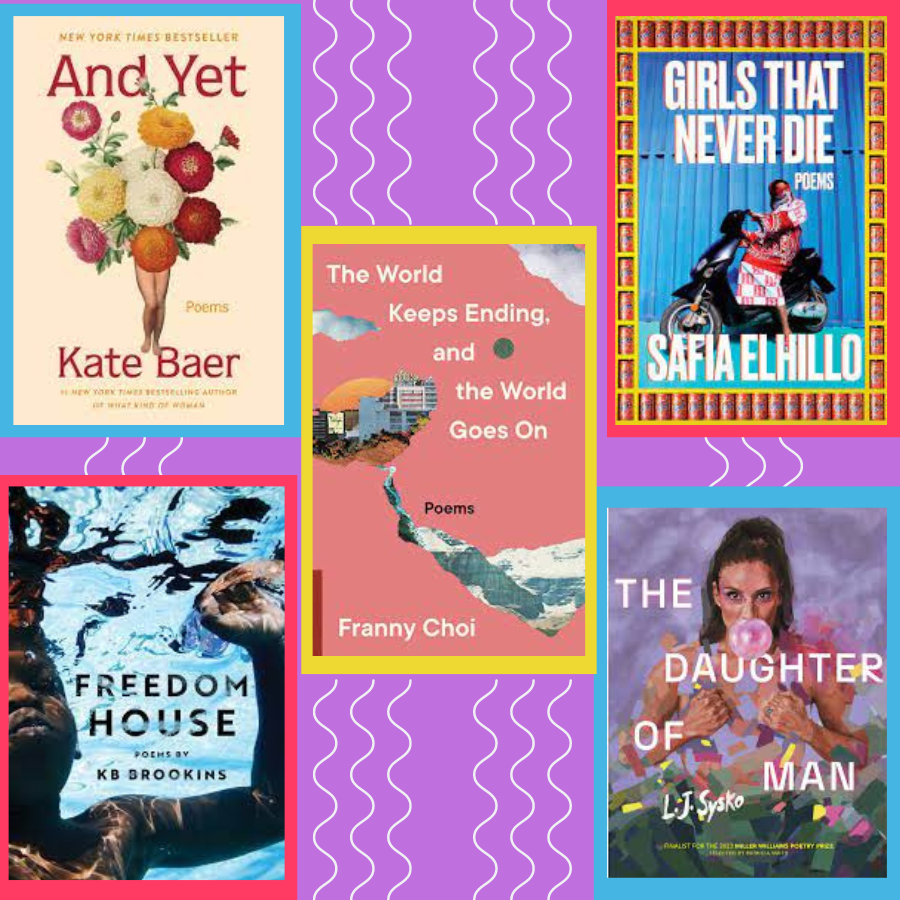

In honor of National Poetry Month, FBC’s book of the month is Rose Quartz. If it leaves you inspired to keep reading, I’ve compiled a list of five new, recent and upcoming poetry books that I loved.

I’m not a poetry expert, but I can always find the value in a beautiful turn of phrase, the way a line of poetry can hit you so hard in the gut or linger with you for days. These books of new poetry are all current, topical, and delve into the poets’ inner and outer worlds. They are deeply personal and often political.

I admire the creative ways these poets approach their subjects in terms of content and form, the way they can take advantage of the space on the page, the way that their language can imitate action, and the way that they can manage to say so much using a few perfectly chosen words.

LJ Sysko’s Daughter of Man

L.J. Sysko’s debut collection, The Daughter of Man riffs on the hero’s journey. The section titles ask us to imagine a heroine as she transforms from maiden to warrior to queen to maven to crone. Sysko explores the power and vulnerability of young womanhood and the way it evolves through maturity, motherhood and beyond through poems that are bursting with biting intelligence and humor. Sometimes playful and sometimes tormented, she experiments with narrative, shape, and form, juxtaposing the every day with the transcendent.

With lines like, “We kept virtue frozen/ like Thin Mints–hard tack/ squirreled away for/ winter’s subsistence,” she takes the familiar and turns it on its head.

The Daughter of Man is often relatable, full of recognizable bits of pop culture from Sysko’s depiction of an ’80s childhood to present. But this is not a light book. As the maiden transforms to warrior, the poems are heavy with references to sexual assault, which it engages hauntingly in relation to Artemsia Gentileschi’s paintings. Sysko also writes from the point of view of a legendary woman who poured water for revolutionary war fighters. She consults myth and asks where Odysseus went and considers Penelope swimming in his absence. This book tells the story of many heroines in ways I’ve never heard them before.

KB Brookins’s Freedom House

Freedom House — KB Brookins’s full length debut — is formally adventurous, full of humor, wit and irony that makes you laugh with familiarity before it breaks your heart. The poems, which center the experience of being being Black, queer and trans in Texas, are sometimes defiant and sometimes dream-like.

Brookins includes a mock CV with the professional summary, “Emerging professional well-versed in being poor. Ready for the next opportunity to fight for my life.” There is a poem in the shape of an Amazon purchase screen and a poem that imagines dinner with John Cena on the moon. They use erasure to make a poem of the original text of Texas Senate abortion bill.

But it is Brookins’s words beyond their well-wrought concepts that move me again and again. Freedom House is a remarkably embodied book. Brookins poignantly depicts the physical experience of being trans and of experiencing bodily change. Their poems are visceral and painful and sometimes full of rage. They are also full of youth, lust, pleasure, and hope.

In “Good Grief,” they write, “Let’s write a future more joyful & less inevitable in segments of leaves./ Anything we dream will be better than this.”

Freedom House, in its way, does just that.

Safia Elhillo’s Girls That Never Die

Girls That Never Die by Safia Elhillo, begins with and is full of the contradictions of Elhillo’s experience of Muslim girlhood in America. The book, which takes its title from an Ol’ Dirty Bastard song, is perfumed with references to jasmine, pomegranate and sandalwood. It is also thick with the memory of a violation, the forced loss of purity that means the loss of so much else in the culture the book describes.

Elhillo takes us across the world–from a Maryland living room to apartments in Cairo, to Syros and Geneva. She shows us the story of a complicated childhood with the benefit of an adult’s knowing. The poems are concerned with Elhillo’s Sudanese heritage and with language, with forgetting Arabic words, and with what Arabic lacks the words for. They are concerned with violence against women and the brutality of shame. They are also concerned with friendship and fun, and full of American pop culture references, from its title to a poem on “Tony Soprano’s Tender Machismo” and how it reminds her of the disguised hardness of men in her life.

Smart and sad and often beautiful, these poems tell the story of many Muslim women–remembering glamorous grandmothers and celebrating her good friends and mourning for girls who were choked with shame, placed into a “reputation-shaped urn.”

“I feel my girlhood gone for generations/my entire line of blood crowded/with exhausted women,” Elhillo writes. Girls That Never Die does those women justice.

Franny Choi’s The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On

The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On by Franny Choi is perfectly titled. It is a beautifully wrought book concerned with the unending series of catastrophes that compose our history and the polycrisis that composes our present, the catastrophes of the every day and also the ones that have defined eras. The book is imbued with a great sense of grief that transcends timelines–a grief over events in Franny Choi’s Korean lineage, and the way the past endures into the present, and into their imagined futures.

In the book’s titular poem, Choi writes, “By the time the apocalypse began, the world had already ended. /It ended every day for a century or two. It ended, and/ another ending /world spun in its place.”

Choi writes about these endings, about war and imperialism and pain. They also write about the ways people and the earth have endured–the way people stand up and fight or take their loved ones and leave, or how a mushroom can bloom out of ruined earth. In the moments where everything ends, Choi shows that these are the moments where something else begins.

Kate Baer’s And Yet

In And Yet, Baer confronts the contradictions of motherhood and the absurdities of our present moment. She celebrates the tender awe she feels towards her children. In “Marvel,” she writes, “you’re the daughter who became a lion in an otherwise soft and ordinary life.”

But she also is honest about the realities of modern motherhood, discussing postpartum depression, aging and the loss of self. Elsewhere she writes, “When someone asks for my ambitions /I have no answer. I only dream of sleep.”

This wry sincerity courses through And Yet, as Baer conjures the desperation of the early pandemic, gun violence, and the everyday crises that make up a life. Baer manages to balance her seriousness with style.

Bonus: If you’re on a Frankenstein kick after finishing Addie Tsai’s Unwieldy Creatures or just are on the lookout for more new poetry, Jessica Cuello’s Yours, Creature, composed of epistolary poems in the voice of Mary Shelley, often addressed to her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, comes out in May.