This post may include affiliate links, which means we make a small commission on any sales. This commission helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thanks for supporting small, independent media!

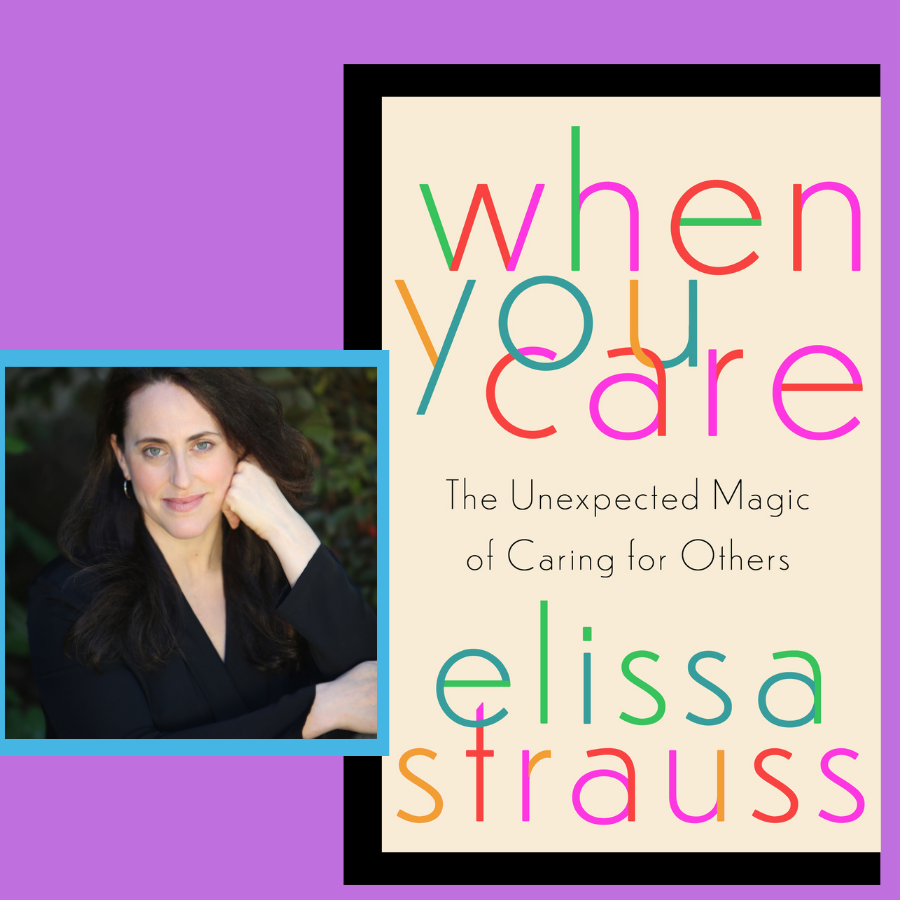

Elissa Strauss’s new book When You Care: The Unexpected Magic of Caring for Others is a moving mediation on the nature of care, infused with research and personal experience. In it, Strauss discusses the history of care, the plight of the modern caretaker, and how we can make caring for others a better experience for everyone. With a subtitle that recalls a famous book that extolls the joys of cleaning, I thought this book might tilt similarly toward self help. It is something decidedly different. When You Care reads like a manifesto at times, at once full of personal details and sprawling in its scope.

Like Angela Garbes and other mothers writing about their experiences, Strauss’s story helps to tell a more overarching one. Strauss argues eruditely for the value of caring for others, while also acknowledging that, in order for everyone to have access to care’s profundity and mutualism, there is a dire need for change in both infrastructure and consciousness.

Strauss took some time to sit down with me to discuss what her brought her to the book, what she learned in the process of writing it, and the value of care in her own life. This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Sam: The book is incredibly well researched. In it, you’re touching on philosophy, neuroscience, personal history, personal interviews—just to name some of the kinds of research you include. Can you tell me a little bit about the process of writing it and how you came to it?

Strauss: Originally, the book came from two parallel experiences. One is that I had written about the politics and culture of feminism and motherhood for a long time, and I reached a point where I felt like I couldn’t write one more paid leave article. I had gotten to the point that was like, why don’t we have this? I can’t live in this universe anymore where I’m advocating for what is to me just the most intuitive thing in the world.

Those articles need to be written. There needs to be someone beating that drum again and again for universal, and affordable and childcare, elder care, paid leave—all this care infrastructure, but I also felt like something deeper was going on, and I was curious about it.

The other thing that happened was that I went into motherhood. As you know, right about at the beginning of the book, there was this sense where I wanted to protect myself from it, this thought that it would make me less interesting. I felt like everyone on Brooklyn playgrounds in 2012 was passing Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work around. In that book, kind of directly and indirectly, selfhood and motherhood are presented as a zero-sum game.

I was realizing that maybe that’s not the case. And maybe actually these two things are linked: maybe the reason we don’t have paid leave is because we also really don’t in our guts appreciate care in this rich, deep way. That was the inspiration for the book. And then, practically speaking, the book really started with the philosophy chapter. I was not a philosophy person ever. I tried it in college, and I really was like, how do these people take what seems like the most interesting conversations in the world, and make them as boring as possible?

Of course that’s not the case universally, but that’s how it felt to me. But getting deep into parenting, I realized what a complicated moral ground it was, both for seeing myself as who I was as a person reflected through my son and how to do right by him. This started with my first; now I have two.

The last layer of it is when you care for someone—I’m still hesitant to say this—you have to put their needs above the needs of others. You cannot care for your children in a way that’s fully equitable to how you care or don’t care for other anyone else’s children. So how do we balance that? How do we make these decisions? I do think relationally about my kids and their privileges, and how that affects other children. Where do I draw those lines? There aren’t easy answers.

Sam: You speak about philosophy and its role in the book. It’s sort of was amazing to me that, halfway through the book, we find out that Eva Feder Kittay is your distant cousin, because I feel like in some ways this book is a distant cousin of sort of the work that she’s doing in emphasizing an ethics of care and a way of looking at the world through relationships. Can you talk a little bit about the philosophy behind the ethics of care?

Strauss: There is this whole corner of philosophy that really emerged in the eighties, which is hard to believe when you think about like this whole history of Western philosophy, and that no one really dug into care or even relationality in a meaningful way in a meaningful way until like 40 years ago.

A psychologist named Carol Gilligan worked on a study on the different stages of moral development at Harvard led by Lawrence Kohlberg. In his study, Kohlberg concluded that women are basically less morally developed than men, because we get stuck in the relational phase of ethics, whereas men mature to a universal stage. He also only studied boys or men like in this. He did not study woman or girls when making this statement. So, in response, Gilligan did research, which led to a book called In a Different Voice, which really introduced this idea of care ethics. And even though she wasn’t exactly doing what we think of as philosophy, it took off in the world of philosophy.

Photo Source: New York University Faculty Page

I also really fell in love with the writing of Nel Noddings. I can’t remember exactly, but she had something like ten kids in this extended station wagon, and they would take road trips. She was very domestic, and she also did this philosophical work. These things were fully integrated for her, and in a way that I feel like it’s still like a model for how to be. Noddings wrote a lot about care as an ethically formative act. That really resonated with me, that our memory of being cared for by our parents and our ability to care for people is like just this, it’s at the heart of what it means to be a good person. From there we can keep building on our understanding of how to do right by others.

She also separates out this idea of caring for and caring about. She says caring for is a direct care relationship—there’s a human being that is dependent on you to live. And then there’s caring about, which is how we can care about other children, children across the world suffering, and both very real and very important.

But she separates the two, and she got in trouble for it. It does sound awful like: I, Elissa Avery Strauss, care more about Auggie and Levi than I do about other children. That just sounds horrible. But, if we actually take care seriously, it’s true. How do I take this feeling I have for my sons, and use it to amplify how I care about other people, while at the same time respecting that the act of care is so big and these relationships that get formed with them are so deep and rich that it will never be the same.

Sam: I found this concept really interesting, but I also found it challenging. There were parts of the book where you talked a little bit about collective care, even in primates who tend to raise their offspring collectively. But you took the time to separate this idea from the experience of, say, a kibbutz. I wonder what something like this means for someone who doesn’t have children. I don’t have children and I’m not in a position where I’m caring for someone right now. Of course, life could go in all sorts of ways. But how can someone who is in a position where they are not caring directly for someone integrate care into their life?

Strauss: Yeah, that’s a great question. My answer is ongoing. I think part of what I was responding to there is rooted in my own Jewish tradition There’s this real proud sense of being part of the collective. But then you can really value a collective without actually respecting caregivers or the work they do. There can be interdependence without respect for care. I was really trying to like push through that in my book that those two things can coexist.

But I think we all live in a thick web of care. We should have independence. These are great, important things. But, on the other hand, how do we get the value of care if we’re not in a clear, distinct care relationship? It would be seeing your relationships through the lens of care, seeing how friendships are also dependency relationships.

If you have parents who are alive, as they get older, every day it’s it becomes more and more of a care relationship. And I think part of the problem in this is that care is so under-theorized and under-defined. I feel like mine is an effort, but it’s hardly a job done, even of defining what a care relationship is. For instance, men are very reluctant to call themselves caregivers because it feels like it’s this very concrete thing or that it’s for women. But they are caregivers. I think we can gain the benefits of care by using that as a lens in all of our relationship. And also by caring for the caregivers in your life.

Sam: I think this plays into discussions you had both in the book and in a recent piece in The Atlantic on codependency and interdependence (Editor’s Note: Behind a pay wall). You talk a little bit about the codependence narrative that we see kind of everywhere where women are really encouraged to set boundaries. But I also feel like sometimes we end up using therapy speak too much with the people in our lives. Can you talk a little bit about why interdependence is a concept and a narrative you’ve come to value more?

Strauss: Yes, with the caveat that I’m not sure there is like a fixed meaning for interdependence. But I think that’s actually part of the fun right?

We came from a culture where there is an expectation that everyone depends on a woman. And women are really tired. We fight it by like erecting these tall walls. Right? So, the correction becomes an over correction, which I see coming through a lot of the language around codependency, and the particularly the way in which codependency kind of metabolized on social media.

One definition of I saw by a prominent voice was like: if someone else is happy and it makes you happy, or if someone else is sad and it makes you sad, you’re codependent. And I’m like, or human.

It’s all written into the kind of history of feminism in the last 50 years. We want to get out of the house; we wanna feel free. We want to go for long hikes in the woods without anyone telling us what to do. I do, too. We want to not feel responsible for the emotions of others.

Maybe because of the patriarchal way and the care-ignorant way that we’ve learned about what it means to be a human what it means to live in a meaningful life has made us write off all those experiences that are inside the home in favor of the experiences outside the home. Inside the home is a place of codependency, where you’re accountable to others, where people need things from you.

For me, interdependence is that middle ground. We understand that we are all connected and we also try to balance the cultivation of self with these connections, while ultimately realizing that those things are not separate. We cultivate the self through connections.

I guess that’s the new having it all: being able to be dependent and independent, all in good measure.

FBC: Something you’ve talked about, and that resonates throughout the book, is that a lot of the joys you talk about coming from caring can only come to fruition when all these structural problems that you’ve been writing about for a while are addressed. Are there places that you find hope in these areas and changes you’ve seen happen?

Strauss: Yes, just this week there was a huge effort in Washington to push a Care Can’t Wait agenda. Biden gave a great speech. I think Biden just says the word “care” a lot more than any President. I guess I’m a words person so I’m biased.

But there was this feeling when I entered this book, I’m in this space that’s under-theorized and under-explored. What is care? More often with men than women, they’ll be like, what is this care you speak of? Just having a shared vocabulary, I think, has been the biggest sign of progress over the last few years.

When Biden says, “care infrastructure,” a lot more people know exactly what he means. I think the care justice movement has been doing slow, steady, beautiful, incremental change—getting paid leave passed in different States and cities and getting Domestic Workers’ Bills of Rights passed.

There’s also been a push for more support for elder care. We had a tax credit during COVID for parents. It stopped but it was very effective when it was in place. There’s movement at the Federal Bureau of economics to find meaningful ways to count care as part of the GDP.

I’m an optimist, so I have to note that. And this is through no effort of my own—I am just a writer reading old theology texts and trying to find what they do or don’t say about care—but all these great activists have been hitting the streets for a long time and there have been meaningful gains.

FBC: What are some of the important histories—particularly activist histories—that you got to learn about and tell through this book?

Strauss: I’m not a scholar of feminism. I think that’s important to say. I’m just a human, Elissa Avery Strauss, born in 1979, experiencing feminism.

I did not experience a feminism that had very nice things to say about motherhood. Whether it’s The Second Sex, whether it’s Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique or even sex positive feminism, Cosmo, or Lean In. None of them talked about motherhood in positive ways. Going into motherhood, a lot of my trepidation and concern was rooted in in my experience of feminism. And one of my favorite parts of writing this book and the research I did was learning about feminist spaces where care was acknowledged.

One example was in the suffragist movement. There was this whole group of women that called themselves municipal housekeepers, sometimes social housekeepers. Their argument was that the wisdom that women get from care is needed at the voting booth. Of course, that also limits women at the same time.

That idea had been lost to time. One of the women from that period said something along the lines of, “A woman’s place, is the home, and the home is everywhere.”

That really resonated. We still think that of what happens in the home as totally separate from what happens outside the home.

There were also a lot of Black feminist activists. We think of women as leaving the home and going to work. But that was really a largely an upper class white trajectory, whereas working class women and women of color were often working outside the home while raising kids.

A lot of those women, most notably welfare rights activist like Johnnie Tillmon, argued for support to stay home with their kids (Editor’s Note: Please do yourself a favor and read Tillmon’s piece “Welfare is a Woman’s Issue“). It’s a whole different facet of feminism that I would have loved to learn about alongside all the other feminisms. Learning about them empowered me and made me see my life as bigger than I may have without them.

Sam: As you mentioned, you start the book as feeling sort of resistant to being one of the moms you saw together in a group or to making motherhood central to your identity. After the process of writing this book and researching it, if you could go back and sort of tell yourself anything, what would you say to yourself as a new mom?

Strauss: First, to really be aware of all my internalized misogyny that made me mom-resistant. Some of it was fair. I wasn’t a big breast feeder. I wasn’t attachment parenting. There was a lot of pressure at that time in Brooklyn to do those things. I don’t disagree with it all, but I think we can resist some of the trends of mom culture. And, for me, it was just this kind of like wholesale dismissal. And I also had this idea that talking about your kids makes you boring. I mean, I really believed that and that’s just so sad to me now.

And also, to understand that I was really going to learn a lot about myself through caring for my kids than I did in like so many other things that are supposed to be the greats epiphany-makers—whether it’s long backpacking and long road trips or meditation retreats. Those are very real, and they really are powerful for a lot of people. And maybe, if I find myself hiking some mountain alone in 10 years, my brain will explode with realizations about myself and life. I don’t want to criticize anything. I just want to add care to the mix. I learned about myself and how I experience the nature of life through care than I have through much else.