Editors Note: Matilda Bilstein Ong is a Feminist Book Club member who besides being an amazing attorney and general overall badass is of the Jewish persuasion. I reached out to her to get some information about Hanukkah from someone in the know, as it were, so here you go! Do some learnin’ and expand your horizons on this, the eve of the second night of Hanukkah.

Jews are an ethno-religious group that make up approximately 0.25% of the total world population. Although not the most significant holiday in Judaism, Hanukkah is the most widely acknowledged by the media and capitalism in the United States. Although there are various ways to spell Hanukkah (Chanukah, or in Spanish: Janùka) due to the transliteration from the Hebrew, Hanukkah has only one meaning in Hebrew “Dedication”, because it celebrates the rededication of the Holy Temple. Hanukkah begins on the 25th of Kislev, and because the Jewish/Hebrew calendar is a lunisolar calendar (which, incidentally is different than a purely lunar calendar), Hanukkah generally falls between late November and late December on the Gregorian calendar. As Jewish days begin and end from sunset to sunset, Hanukkah 2021 begins on the evening of Sunday, November 28.

Historical Background

Because Hanukkah is not a biblical festival commanded in the Torah, it is considered a minor (but not unimportant) festival, but it is also marked by special observances at home and at synagogue to commemorate the resilience of the Jewish people and the Jewish resistance against assimilation. In 198 BCE, after two decades of fighting, Judea passed into the control of Seleucid (Syrian-Greek) Antiochus III who ruled from 223 BCE to 187 BCE. From 175 BCE to 163 BCE, the Kingdom of Judah was ruled by his son, King Antiochus IV Epiphanes. This marked the beginning of the Hellenization of Jerusalem. Antiochus IV deposed the High Priest Onias III and replaced him with his brother Jason, who received instructions to introduce Greek institutions to Jerusalem.

Three years later, upon the succession of Menelaus as High Priest, unrest and protests broke out. Thinking that a rebellion had broken out, Antiochus IV abolished Jewish law in Judea. Jews were no longer allowed to study Torah, and an altar and statue of Zeus was set up in the Holy Temple. Seleucid people and Jewish Hellenizers (sympathizers) forced Jews to eat pork, refrain from circumcision and from observing Shabbat, and to turn in Torah scrolls for destruction. The story goes that to trick the Greeks, Jewish children and their teachers would pretend to play with a spinning top (dreidel in Yiddish) when studying Torah in secret. Due to these prohibitions, a revolt broke out. The first group of fighters were slaughtered due to refusing to fight on Shabbat, and so the next stage of Jewish opposition was the emergence of a group under Mattathias, a priest from Modiin. When Mattathias died, the leadership of the armed revolt was taken over by one of his sons, Judah the Maccabee (Judah the Hammer).

After years of fighting, the Maccabean fighters regained the Temple Mount in 164 BCE and by December of that year the Temple was purified and reconsecrated. It is generally believed that when they sought to light the Temple’s Menorah (the seven-branched candelabrum), they found only a single jar of olive oil that had escaped contamination by the Greeks. Miraculously, they lit the menorah and the one-day supply of oil lasted for eight days, until new oil could be prepared under the laws of halakha (ritual purity). To commemorate and publicize these miracles, the sages instituted an eight-day festival (Hanukkah) and soon afterward the Seleucid government gave up its policy of religious repression.

Nuts and Bolts of Celebration

Over the centuries, Hanukkah has been generally celebrated by lighting a nine-branched menorah (also called a Hannukiyah), increasing the number of lights each evening to commemorate the eight days that the oil lasted, by using a helper candle (called the Shamash) as the candles are supposed to be purely celebratory and not used to light other candles. There are special blessings to commemorate the miracle of reclaiming the Temple and the continuance of a Jewish community.

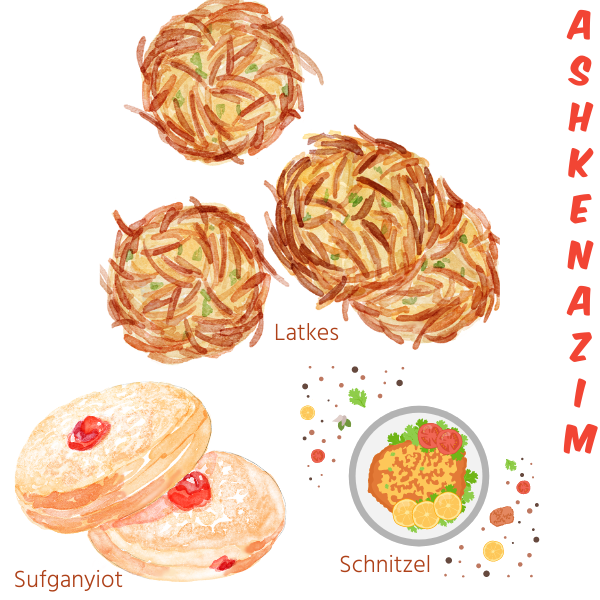

Different Jewish communities around the world eat various types of fried foods to celebrate the miracle of oil. For example, most Ashkenazi Jews (Jews who were exiled to Eastern Europe) eat latkes (potato pancakes), schnitzel, and sufganiyot (jelly-filled donuts).

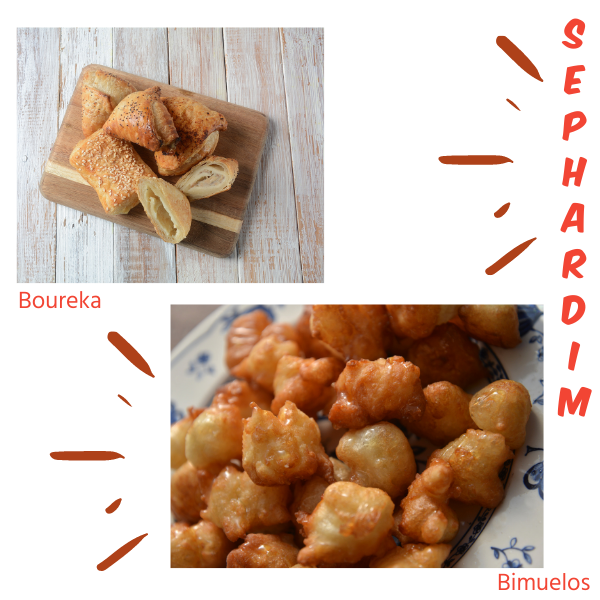

Sephardic Jews (Jews who were exiled to Spain and escaped elsewhere after the Inquisition) generally eat bourekas (savory filled pastries) and bimuelos. Jews in Latin America (Ashkenazi or Sephardi) may also eat fried plantains or other local fried foods.

Depending on the country, Mizrahi Jews (Jews who were exiled to Morocco, Tunisia, Turkey, Syria, etc.) will eat foods like kibbet yatkeen, fritas de prasa, cassola, and sfenj or spanj (similar to donuts). It was also customary for Yemenite Jewish women to wear clothing decorated with bells and hold bells in their hand to play music in celebration.

Hanukkah in the United States

Despite it being a relatively minor holiday, and ironically, due its proximity to Christmas, Hanukkah has attained major cultural significance in the United States to adapt to American life. Jewish families did this to maintain a Jewish identity which is distinct from mainline Christian American culture. For example, gift giving is a relatively new tradition that is not observed by Jewish communities outside of the US. There is also the recent presence of Hanukkah bushes as a counterpart to Christmas trees, although this is generally discouraged by most Rabbis.

Given this history, I would like to note that Liz Kleinrock at Teach and Transform has some recommended resources for decentering Christmas in the classroom to make it more inclusive for non-Christians kids in December but is also helpful for adults to keep in mind in other settings!

A traditional hymn sung on Hanukkah is Maos Tzur – the linked version is by Leslie Odom, Jr. and his wife (fellow Member of the Tribe) Nicolette Robinson. Idina Menzel also does a beautiful version of Ocho Kandelikas which is a Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) Hanukkah song. And my personal favorite 2020 hit: Puppy for Hanukkah by Daveed Diggs.

Recommended Reading

My Jewish Year: 18 Holidays, One Wondering Jew by Abigail Pogrebin

Here All Along: Finding Meaning, Spirituality and a Deeper Connection to Life in Judaism After Finally Choosing to Look There by Sarah Hurwitz

Jewish Literacy by Rabbi Joseph Telushkin

Jewish People, Jewish Thought: The Jewish Experience in History by Robert Seltzer

A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice by Isaac Klein

Definitely no ketchup on latkes. What a shonde! Sour cream or apple sauce, tho and lox, if you’re bougie (which I am).