This post may include affiliate links, which means we make a small commission on any sales. This commission helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thanks for supporting small, independent media!

“Reclaiming the Canon” is a series of posts that aims to bring attention to historical women who are often excluded from the narrative of their field — whether in literature, music, science, or other areas. Each post features a woman whose name we feel everyone should know. Readers are strongly encouraged to explore further resources, spend quality time with primary sources when possible, and self-educate — because re-claiming the canon starts with you!

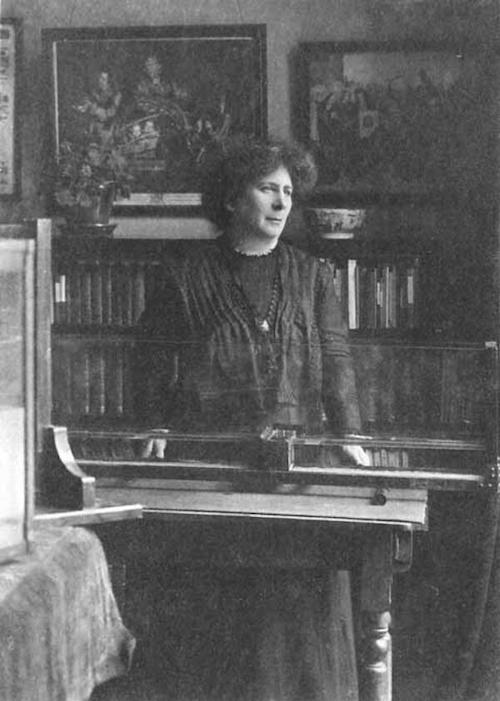

Who Was Hertha Ayrton?

Hertha Ayrton was a British scientist and inventor who lived from 1854-1923. Active as an engineer, physicist, and mathematician, Ayrton made significant contributions to the study of electric arcs and ripple marks in sand and water. She registered a total of twenty-six patents throughout her career, and she was the first woman to be awarded the prestigious Hughes Medal by the Royal Society of London.

Ayrton was also a prominent suffragette who was passionate about women’s equality. She joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) as a teenager. Later, many suffragettes who had gone on hunger strikes—including political activist Emmeline Pankhurst—would recuperate at Ayrton’s home.

Her Life

Born Phoebe Sarah Marks in Portsea, Hampshire in England, young Ayrton was the third child of a Polish Jewish watchmaker and a seamstress. When her father died in 1861, she helped care for her five younger siblings. At age nine she moved to a relative’s home in London, where she was introduced to science and mathematics before attending Girton College (the first women’s college in Cambridge). She was known in school for her fiery and crude personality. In her teen years, she renounced her Judaism and became agnostic, taking the name “Hertha” for herself. Hertha was the earth goddess in Algernon Charles Swinburne’s poem “Hertha,” which criticized organized religion.

Cambridge did not award degrees to women at the time, but the University of London awarded a Bachelor of Science degree to Ayrton in 1881. After college, Ayrton ran a club for working women, taught high school, and published her solutions to mathematical problems. In 1884, at the age of thirty and with the financial support of feminist activists and philanthropists Louisa Goldsmid and Barbara Bodichon, Ayrton patented the line-divider, an instrument for dividing a line into equal parts used by artists, engineers, and architects.

That same year, Ayrton began attending classes on electricity, and eventually married William Edward Ayrton, her professor. She assisted him with his experiments and wrote her own articles for The Electrician. In 1899, Ayrton became the first woman to read her own paper before the Institute of Electrical Engineers (IEE), and soon after became the first female member of the IEE.

Ayrton also petitioned to read her paper “The Mechanism of the Electric Arc” for the Royal Society of London (which was and is a prominent scientific academy), but she was not allowed due to her gender. After she published her book The Electric Arc in 1902, Ayrton was proposed as a Fellow of the Royal Society. She was turned down due to her status as a married woman, meaning she had no legal existence under British law. (!) Nonetheless, in 1906 she became the first woman to win the Royal Society’s prestigious Hughes Medal. (As of this writing, only two other women have received the award, Michele Dougherty in 2008 and Clare Grey in 2020.)

Her Contribution

Hertha Ayrton made invaluable contributions to both the scientific community and women’s movement of her time. After she spoke at the International Electrical Congress in Paris in 1900, the British Association for the Advancement of Science started allowing women on their committees. Ayrton also helped found the International Federation of University Women in 1919 as well as the National Union of Scientific Workers in 1920. Her work led to significant improvements in the efficiency and design of electric illumination, and her Ayrton “flapper fan”—originally intended to dispel poison and gas in World War I trenches—was eventually adapted to improve ventilation for workers in mines and sewers.

In 2010, a panel of female fellows of the Royal Society—which Ayrton was never allowed to be a member of—voted Ayrton to be one of the ten most influential British women in the history of science.

In Her Words

Hertha was close friends with Marie Curie, and she taught mathematics to Marie’s daughter. In response to the British press suggesting that Marie Curie’s work was actually the work of her husband, Ayrton wrote:

“Errors are notoriously hard to kill, but an error that ascribes to a man what was actually the work of a woman has more lives than a cat.”

-Hertha Ayrton

Further Resources

Read more about Hertha Ayrton’s fascinating life over at Massive Science.

Watch the BBC’s “The woman who tamed lightning” to better understand Ayrton’s contribution to electricity.

Want a deeper dive? Go straight to the source with Ayrton’s book The Electric Arc.

Learn more about Hertha Ayrton and other women in science with IFLScience.

If you need a reading break, check out this podcast about Hertha Ayrton.