This post may include affiliate links, which means we make a small commission on any sales. This commission helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thanks for supporting small, independent media!

We stood in the lap lanes of our local pool, bobbing gently, skin pimpling in the cold as we stared expectantly up at the water aerobics instructor. He stood before us in loose shorts and a T-shirt, his sneakered feet clad in white socks that were pulled taut up the length of his shins. His gray moustache glinted mutely in the twilight.

The man looked out over the water and stepped closer to the lip of the pool, bringing his hands together in front of him. He gave a small bow. “And so it begins.”

He bent down to the boom box sitting on the concrete and pressed “play.” We spent the next 45 minutes dragging our arms through the water, kicking our legs out and in, slow-motion hopping in our one-piece bathing suits with side ruching as dance music floated on the air. At one point, we twisted from side to side, swinging our arms with us, dragging the water from one side to the other, a move that would later wake me up in the middle of the night, muscles screaming. As my arms glided through the water, the sky darkening above me, I couldn’t help but smile.

I felt like a kid again. I felt like a ballerina. I felt free.

Exercise as a Means to Control the Body

I’ve never really been an athletic person. When I was growing up, my parents had me try a rotating array of physical activities. I was terrible at all of them. I wasn’t coordinated enough for gymnastics or cheerleading or dance. I wasn’t aggressive enough for basketball. I even sucked at bowling. Things that required any level of endurance were also a no-go. I mean, I just didn’t have any.

Still, as I reached my teens and my early 20s, my mother continued to encourage some level of engagement with exercise. She took me to her weekly callanetics classes. She signed me up for a gym membership. We went on walks in the evenings, our arms pumping vigorously at our sides.

These attempts at fitness were, of course, paired with intermittent Weight Watchers memberships. My mother had always, to some extent, been held in thrall by diet culture, had restricted her food intake so as to keep herself small and trim. When I began to gain weight steadily in college, I know she was alarmed. I know she saw me as a problem to be fixed.

Once upon a time (according to Danielle Friedman’s Let’s Get Physical), women’s fitness was frowned upon and those who opened up that world for their peers were considered trailblazers. But exercise culture has long since become wrapped up in systemically-driven and internalized fatphobia. When my mother dragged me to the gym or to her fitness classes, I knew she marked my “success” at these activities by the number on the scale and the size of my clothes. And so, while I did receive some small measure of satisfaction in these activities that was not tied to my weight, this satisfaction was tempered by the fact that I was still failing to make myself smaller.

Beginning to Disconnect Movement from Weight Loss

When I first tried yoga at the age of 30, I had long since internalized the idea that my body was a problem. How could I not? It was embedded in the culture. It was embedded in my home.

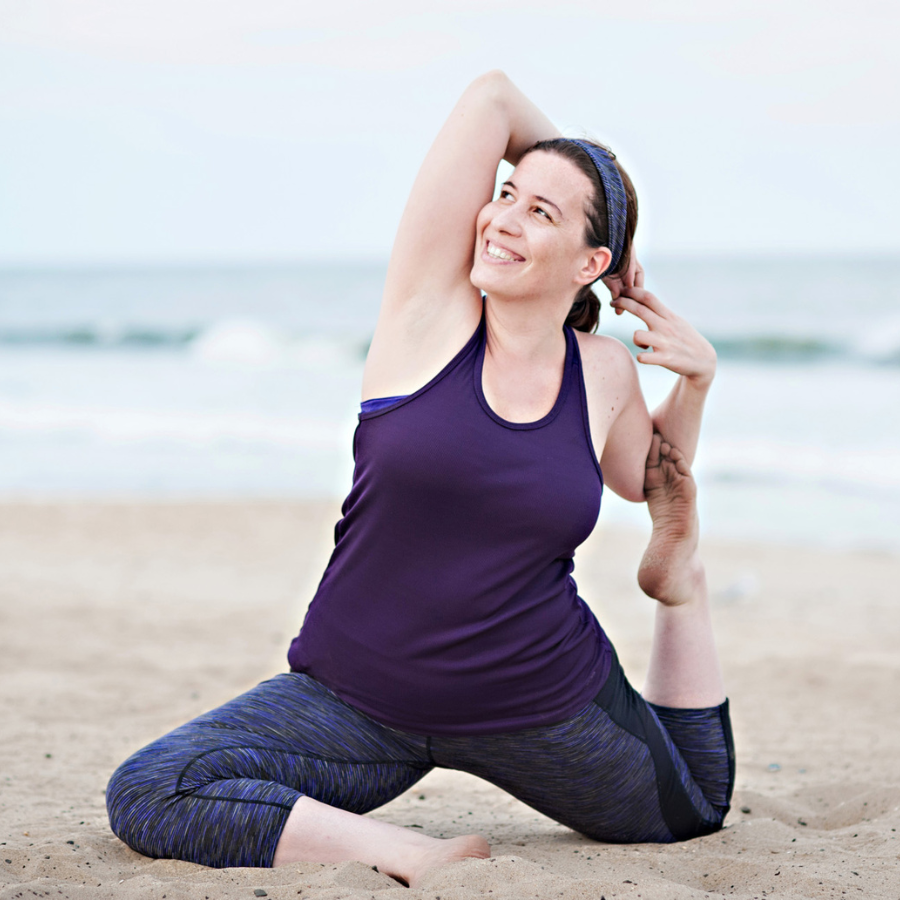

So yeah, I thought yoga might help me me attain the body I thought I should have. But the more I did yoga, the more I saw the other benefits it carried, benefits like strength, flexibility, increased energy, and improved mental health. For these reasons, yoga asana was the first form of “exercise” that stuck.

(Note: I write this knowing that yoga is not intended to be a form of exercise. This is a deeply Westernized approach to the practice. Perhaps it’s more accurate to say that yoga asana, in particular, is the first physical, movement-based practice that stuck, and I loved yoga all the more for its other limbs, including pranayama and dharana.)

In my first years practicing yoga, I attended classes four to six times a week. I was just so hungry for the positive feelings I got from moving through the postures and sitting with my breath. When I became pregnant at the age of 33, I was in the best shape of my life, never mind my expanding belly, breasts, and ankles. I was still fat (well, even fatter because of the pregnancy) and I felt phenomenal.

Exploring Body Neutrality During the Pandemic

Despite a growing appreciation for everything of which my body was capable, I still struggled to love myself. I grasped toward body positivity only to stumble back into body hate. It wasn’t until several years later, when we were in the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic, that I began to cautiously explore body neutrality and the concept of health at every size through books like Caroline Dooner’s The F*ck It Diet and Virgie Tovar’s You Have the Right to Remain Fat.

Maybe it just felt safer to let my body take the lead at a time when we were all tossing our underwire bras and our hard pants, embracing comfort and being kinder to our bodies. Whatever the reason, I stopped policing my eating habits and began to trust in the wisdom of my own appetite. As far as exercise goes, I used it as a salve for my anger, anxiety, and overwhelm, rather than as a means to transform how I looked. When I taught Zoom yoga from my living room on Sunday mornings, I leaned into postures and practices that helped me find temporary peace, and that stretched out my perpetually tight muscles, assuming those who attended the class could benefit from the same. During my daily basement rowing machine sessions, I pushed and sweated through my rage. During the long walks I took with a friend several nights a week, I allowed myself to glory in the feeling of joyful movement, and in the fresh air, and in the connection I was able to enjoy with another human being outside my immediate family.

Then I injured my ankle last summer and it refused to heal and, when I finally went to my doctor, she told me I had to stop doing all of that.

Getting Giddy from Joyful Movement

My doctor suggested swimming. Fine. Whatever. I wasn’t much of a swimmer, but I missed moving my body. One day, however, while executing my poor excuse for a breaststroke in one of the lap lanes at the local pool, I told my friend that I wished we could just find a water aerobics class.

Back in 2019, before everything went to hell, I had attended a week-long writing residency on Martha’s Vineyard, and had walked to the beach every morning to do water aerobics in the ocean with the local Polar Bear club. It was the best part of my day, and I still look back on this experience with extreme fondness and intense wistfulness.

In my 20s (that’s over 20 years ago for everyone who’s keeping track), I’d had a fantastic time trying belly dancing, hoop dancing and, a handful of times, Dance Dance Party Party. But my time with the Polar Bears was the first experience I’d had with purely joyful movement in a very long while.

I wanted to reclaim that feeling.

Writer Cindy DiTiberio wrote this great piece last year on how women are often divorced from desire. She starts by focusing on sexual desire, on the difficulty of taking or asking for what we want. But she eventually winds her way to all the forms of pleasure we do not allow ourselves to experience.

“We are capable of feeling good, throughout the day, with no cost to anyone else and yet we rob ourselves of these moments,” she writes. “We get so caught up in productivity, crossing one more thing off the to-do list, throwing in one more load of laundry, that we forget to stop and tend to ourselves. What, in this moment, could I do to make myself feel good? How could I make myself more comfortable?”

She goes on later in the piece to point out that “[w]hen we learn not to want, we learn not to hunger. We tamp down our appetite – for food, for pleasure, for freedom. … Maybe we are unfamiliar with pleasure because we haven’t allowed ourselves to be hungry.”

But, my god, I was so hungry. And if I was finally allowing myself to indulge my hunger for delicious food, whenever the hell I wanted it, it stood to reason that I should also indulge my hunger for movement that did not operate as a form of productivity, that was not a goal-oriented activity intended to “improve” my body (a concept that, of course, presupposes that my body is less-than).

Unfortunately, it was too late in the season to find an open water aerobics class. But when my friend sent me a flyer for twilight water aerobics nearly a year later, I legit squeed.

Cut to just a few weeks ago. As we neared the end of our first water aerobics class of the season, a class during which my boob had slow motion floated out of my top at one point when we did submerged jumping jacks (lol), our instructor ejected his dance mix and placed another CD into the boom box. He looked out across the lanes of the pool, where we stood bobbing up and down, all anticipation.

“It’s time to put it all together,” he said.

We waited, leaning into the silence. Finally, the first strains of Cole Porter’s Can-Can song danced on the air.

Our instructor directed us through a choreographed series of kicks—front, back, to the side, across, front, back, to the side, across. I bumbled my way through the sequence, dropping counts, falling over in slow motion, making a glorious mess of things.

“Kick! Kick! Kick! Kick!” he yelled at the climax, as the song drew close to the end, as our legs pressed out in front of us over and over again.

As we hurtled toward that final chord, we all knew what to do. We planted our feet. Flung our arms into the air.

“Ta-daaa!” we shouted, the water erupting into liquid fireworks.

It was perfect.