Nearly two years ago, I wrote a book about my sex life. More specifically, it was about the ways in which our culture treats female sexuality like a dirty word, framed within the context of my own sexual journey, which included coercive sex within the context of a sexually and emotionally abusive relationship and an ongoing attempt to fix what I saw as broken within myself, thanks to “low” libido levels and pain during penetrative intercourse.

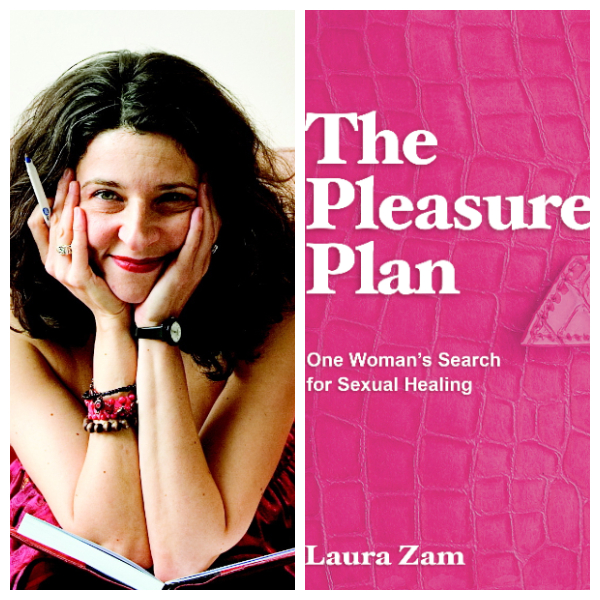

A few months ago, a colleague of mine introduced me to Laura Zam. Her book, The Pleasure Plan (which recently came out), was about her own journey of sexual healing after a lifetime of painful sex and nonexistent desire. To say I connected with her story is an understatement.

After reading her book, I had to chat with Laura about female sexuality and gender imbalances within the sexual health field and all that fun stuff. Here’s our conversation, edited for space and clarity:

Steph Auteri: You write so engagingly of your inability to figure out why in heck sex is so painful and, after finding a diagnosis, the difficulty in “fixing” the problem. This journey sounds similar to the journey many women undergo when it comes to unexplainable issues with their ladyparts.

With more and more stories like this gaining visibility — around endometriosis, vaginismus, vestibulitis, and on and on — why does it seem like nothing is changing?

Or is it changing and I’m just cynical?

Laura Zam: I see change. But we need more.

I was at Esther Perel’s Sessions Live [an annual live salon for therapists, coaches, and other relationship professionals] and a sex educator led us in an exercise where you imagine something really delicious to eat and you just notice your body. Even just imagining the food, your salivary glands can activate and you feel your body move toward it. Then, you imagine something you hate to eat and you notice your body and how it retracts. The body moves away from it.

This is dyspareunia [genital pain that occurs during penetrative intercourse]. It makes total sense that if somebody has trauma, the body would just retract. It’s a very commonsensical process, but I feel that physicians are missing it.

SA: How do you feel these healthcare inequities tie into the role of female desire in our culture and, for that matter, what IS the role of female desire in our culture?

LZ: I think seeking pleasure is fundamentally a justice issue. The default is a female body being used for somebody else’s pleasure, which is a form of dehumanization. I think that’s why we sometimes respond the way we do physically. Especially for populations that have sustained so much sexual trauma, it perpetuates itself in really horrible ways.

Female desire… we don’t really know what that looks like as a society. We see performative representations in porn. I think it’s extremely difficult for most women to not perform. I think many women don’t even have a firm grasp on what is authentically pleasurable because we’re so concerned with pleasing our partners. We have to stop privileging this phallocentric idea of sex.

SA: Honing in on our relationships, I couldn’t help but draw parallels between your life and my own, and the complicated feelings we can’t help but have around sex within the context of our marriages. When you’re struggling with pain or “low” desire or both, there’s an endless cycle of guilt and frustration and anger and guilt and frustration and anger and it just seems to kill marital intimacy.

You write, “I want to be more than just a friction machine,” and I was like yeeessss this is exactly how I feel. So what would you say to couples trying to negotiate this rocky road where they want to maintain intimacy with their partner but they also need to take care of themselves?

LZ: What I recommend is that the person who feels at a disadvantage… that person gets very clear with what might work for them. In my book, I recommend a pleasure hour as an ongoing practice [an hour during which one can explore their sexuality solo]. We can get buried under the pressure of having to perform for our partners or please our partners and it can be hard to know where pleasure might reside divorced from that. A solo practice is important. And then you can bring that to your partnership.

And it’s a difficult conversation that can be framed in a positive light, rather than, “Let me tell you why sex hasn’t been working for me for the past 12 years and I forgot to tell you but I hate having sex with you!” Instead, it could be more like, “I’m starting to get some clarity around what I like sexually and there are some things I want to try together.”

I think it’s about opening up that portal to start having a conversation. It’s not immediately redefining the sexual experience but starting to introduce that you want to try something else. Seeing how you can stay present and really advocate for that which is pleasurable. It’s looking at sex not as a script but as an improvisation.

SA: Books and essays about these experiences are becoming more ubiquitous. What do you think drives this desire for women like us to share our stories in such a public way?

LZ: It’s so private and vulnerable. I don’t know what’s driving you, but what’s driving me is fury. It’s my activism. Once I started talking about this, I felt like I stepped over a shame line and I felt a tremendous amount of freedom, like, “Oh, I can talk about anything I want.”

I feel that there’s such a criminal lack of sex ed out there. I think a lot of us are reclaiming our bodies and, through knowledge, helping other people.

SA: Who are some of your favorite writers in this space? Which books have blown you away or made you feel particularly seen?

LZ: Definitely Come As You Are [by Emily Nagoski] is a really seminal book. I like Sheri Winston’s book, Women’s Anatomy of Arousal. I think the Dodson and Ross website is just really, really good. It’s a go-to for me. Then there’s sex therapist Laura Berman’s book, Loving Sex, which doesn’t go into a lot of depth about female sexual problems or challenges, which is telling about how the field has changed, but it’s a very beautiful book about intimacy and finding this mutual pleasure and I think it offers couples a lot of variety. I think her book is an interesting book and brave for talking about these issues.

SA: What do you think is still missing in this conversation?

LZ: I think there are areas that are still not really talked about openly. I think that pelvic pain is looked at from a diagnostic point of view. Either you have something that could account for this or you don’t. I think we need more conversation around what it means to have not only pain but to have some kind of physically uncomfortable situation and know that there are lots of culprits that could be part of that: if the position is wrong, if there’s not enough lubrication or arousal, the zealousness of the thrusting could be problematic…

So, in centuries past, it was all about “just be quiet and just lie there and just let him do his thing.” And I think we have a notion that we are sex-positive as a society and so we’ve left that behind. And I think it still exists almost to the same degree. And the reason it exists is that we don’t feel that we’re entitled to not have pain.

But I’m heartened by all of these books [coming out lately]. This is the new feminism.

If you’re interested in further reading on sexual pain, desire, strengthening your sexually intimate relationships, and how female sexuality is treated in our culture, may I present:

- Sexual Healing by Barbara Keesling, Ph.D.

- When Sex Hurts by Andrew Goldstein MD, Caroline Pukall Ph.D., and Irwin Goldstein MD

- Healing Painful Sex by Deborah Coady, MD and Nancy Fish, MSW, MPH

- Because It Feels Good by Debby Herbenick, Ph.D.

- Pleasure Activism by adrienne maree brown

- Sexual Intimacy for Women by Glenda Corwin

- The Ultimate Guide to Sex and Disability by Miriam Kaufman, MD, Cory Silverberg, and Fran Odette

- Girl Sex 101 by Allison Moon and kd diamond

- Black LGBT Health in the United States by Lourdes Dolores Follins and Jonathan Mathias Lassiter

- Stolen Women by Gail Wyatt

- Black Sexual Politics by Patricia Hill Collins

- Longing to Tell by Tricia Rose