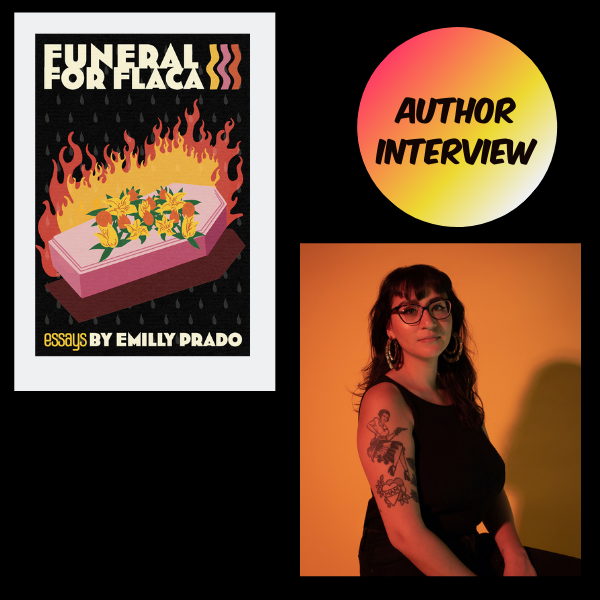

Emilly Giselle Prado is a writer, community organizer, and the Director of Youth Programs at Literary Arts in Portland, Oregon with roots in the San Francisco Bay Area and Michoacán, Mexico. She is the author of youth non-fiction title, Examining Assimilation. Her debut essay collection, Funeral for Flaca, is forthcoming with Future Tense Books on July 1, 2021. With conversational and lyrical language, this Chicana coming-of-age essay collection is poignant, tackling themes such as racism, growing up as a brown student in mostly-white Californian schools, battling with an eating disorder and body image, surviving sexual assault and a mental health crisis, and finding her identity. Emilly’s essays also offer a peek into the California of her childhood, the Portland which is her current residence, and her Mexican family, all with generous references to popular culture. You can also listen to the playlist accompanying the book.

Emilly also moonlights as DJ Mami Miami with Noche Libre, the Latinx DJ collective she co-founded in 2017. I sat down with her to discuss her essays—each titled after a song like a playlist, her use of Spanish in the collection, and how she was writing during the pandemic.

Rashmila Maiti: As this is for a book club, what books are you currently reading? What are some of your all-time favorite books?

Emilly Prado: I am currently reading Milk Blood Heat, the debut collection by Dantiel W. Moniz. I pick a word of the year sometimes and ‘boundaries’ is my word for 2021 so my other read, Boundaries & Protection by Pixie Lighthorse, is exciting. I am learning more about boundary setting. I am also reading The Book of Delights by Ross Gay. Recently, In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado really resonated with me, in terms of the context of the book and how much it plays with structure. Also, All About Love by bell hooks and This Bridge Called My Back edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa are books that I come back to and re-read.

RM: Which is your favorite essay from your collection and why?

EP: I feel like picking a favorite essay from the collection feels like trying to pick which part of my body I love the most. On the flip side, it feels like which part of my body can I do without. Because these are personal essays, I feel like they occupy certain places in my body where they live. One of the essays about sexual assault brings memories of a grazed thigh. I think of my fingers tracing my ex-partner’s hands in the essay about his hospitalization. Many others, of course, are felt in my heart. I have trained by brain to try to love all pieces of my body, and so it feels like a disservice to choose a favorite. The collection is more of linked essays, than stand-alone essays too. I feel that they really need each other to work.

RM: Funeral for Flaca is an unusual title and you discuss it toward the end of the collection. Can you tell us a bit more about the title?

EP: Flaca is the nickname that my family called me but that my dad gave me. Growing up, I was a naturally thin child. One of the central pieces of the collection is my relationship to myself and to my body. In high school, I developed an eating disorder and, in retrospect, a part of me held on to what it meant to embody flaca. Later, through growing up, partly because of medication that I was taking in order to recover from a manic episode, and learning not to be restrictive of my diet, all these factors led me to no longer be considered flaca. And then I noticed that my dad did not call me Flaca anymore, and I had to I learn to not make my pursuit of flaca, subconsciously or consciously, be a central focus in my life. Funeral for Flaca is partly paying respect to that nickname but also, when I think about funerals, I think about death and laying to rest. I had come to place in my life where I needed to be able to put that nickname to rest. Flaca was also about my relationship to my dad. For a long time, the nickname was one of the constants in my relationship with my dad. In some ways, the funeral part of the title is a shedding of that connection. In life cycles of humans and the world around us, there often needs to be a cleansing or a burning to make space for what’s next.

RM: What is your personal and cultural relationship to death?

EP: I am a first-and-half generation Mexican American. My mom was born in Mexico and my dad was born in the US but grew up in Mexico. The celebration known as Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) has been celebrated and highlighted in recent years within the US, popularized with films like Coco and general commercialization. But, it is a very visually and symbolically beautiful holiday with strong Indigenous roots and my family did not celebrate it growing up. I started celebrating Día de los Muertos after I came to Portland in 2009. I first attended events and later was involved in hosting events; I collaborated with a cousin to organize a traditional procession, where we would walk to a cemetery and do an event with face painting and music. I was really interested in getting connected with Día de los Muertos and death in general because growing up, I was afraid of death. It was terrifying to me. There’s still a part of my brain that can’t handle thinking too closely about what will happen after my death. I think about the fears that I have had, and try to face and overcome them. It’s going to feel a lot better to live this life with acceptance that death is inevitable. With that, what are the things we can do to collectively or individually grieve and remember?

The cover artist of my book, Francisco Morales, a Latinx artist based in Portland, had the idea for the flames. In Mexican tradition, you bury the body but I liked the idea that even in paying homage to Día de los Muertos and my improving relationship with death, the visually striking flames were an homage to other cultures that cremate their dead. I would probably want to be cremated too. So it’s a modernization or reinterpretation of tradition—it’s what my book is about: not only my experiences and culture, but figuring out what I believe in.

The back cover of the book will also have a traditional ofrenda—an altar with different foods and symbolism, as another connection to Día de los Muertos and to food which is an essential theme in the essays and my culture.

RM: What inspired you to write this poignant essay collection?

EP: I was a student at the Independent Publishing Resource Center (IPRC) in Portland, interested to know more about creative writing and book making. I have known for a long time that I wanted to be a writer in some capacity and I did not come to the realization that I could feasibly pursue studying it until after I was an undergraduate. I learned a lot from community writing workshops and a Bitch Media internship on how to transition to write for the general reader as opposed to academia, but I wanted to take the year-long workshop at the IPRC to get more experience. I set out to write some essays and thought it would be a small zine. I started to map out different topics and it grew from there. After I self-published that DIY version where I hand-bound and designed everything, I connected with Kevin Sampsell from Future Tense Books. After carrying it at Powell’s, he was interested in helping me put it out again in a more formal way. One of the coolest things about the collection is that it grew organically. Because I never thought it would be more than a zine, I didn’t have much fear while I was writing it. I thought only my friends will read it, maybe.

With the formal release at Future Tense, I had room to revise and add more essays. And suddenly, it was 50,000 words which was I would have been really afraid to tackle as a goal from the get-go. I always thought that my first book would be a traditional narrative memoir that reads like a novel and I still want to write that book. In some ways, I feel like these memories were calling me, and I needed to excavate them in the essays before I could make space for the memoir that I will be writing towards again soon.

RM: How has your experience living in California and Portland, OR influenced this essay collection?

EP: While it’s hard to directly point to how each place influenced the collection, most of the essays do take place in either California or Oregon. The Bay Area is where I grew up and because my essays use a voice tethered to the time period I’m writing about as much as possible, you’ll see some Bay Area slang and references in the earlier essays. I grew up spending a lot of time with family—the bulk of which grew up in Redwood City—and I witnessed how different a town’s culture could be, even just five miles apart, having grown up primarily in Belmont which demographically skews older, more affluent, and white. I often wished I was living in Redwood City which had more Latinx people and even a Little Mexico where the signs are all in Spanish and you can easily get homey foods like morisqueta or menudo and hand-made tortillas.

In addition to being called Flaca growing up, I was also called the morenita, or the little brown one, because I was the darkest in my family. I don’t write about that in the collection, but as adults my siblings and I have talked about our experiences growing up and my brother and sister who were raised with me in Belmont didn’t experience as much outright racism as I did. Not that they didn’t experience any racism or microagressions, but our experiences were markedly different. So I think our environment—both the place and perhaps the specific kids we hung out with—absolutely had everything to do with those differences. I think that I had grown up in Redwood City, or another browner place, my brownness wouldn’t have stood out so much. I craved the invisibility of “being normal” for most of my life.

And yet I ended up in Portland! Living here at first was also really hard and isolating, but two friends of color moved up within six months of my move, and nowadays I actually am surrounded by so many amazing BIPOC friends and a partner. So the “Portland is so white” narrative doesn’t reflect my Portland. There are many intentional spaces for BIPOC that I’m grateful to be part of, plus if you look at the public school demographics which hover around 44% of students being BIPOC, the future of a much more diverse Portland is upon us.

RM: Can you tell us something about your choice of using the Spanish language in the essays without a glossary or a translation?

EP: Spanish is my first language. I didn’t learn English fluently until I started kindergarten. There was also a period in my life when I rejected speaking Spanish and wanted to only speak English. I was embarrassed by Spanish. So this collection includes Spanish as it is something that I have come to love again. My grandmother remembers her own grandmother speaking an indigenous language, but those have been lost in my family. I would have loved to include those if I knew them. Spanish is the language that connects to my culture and family on both sides. I did not want to include a glossary or a translation because this book is for first and foremost for thirteen-year-old me. I want to normalize the use of Spanish because it’s second nature to me. And also, I have read so many English books where I did not understand all the words, and look it up if I wanted to learn it. I think that’s beautiful and a part of growing an understanding of different languages. Including a translation would mean to write a book with a reader who doesn’t speak Spanish and that could also be writing through a white lens. I did not want to do that for this book. There are also words in Spanish, and other languages, that are much more succinct which would be lost in translation.

RM: I enjoyed the references to popular culture and the photographs in the essays. Any particular decision behind that?

EP: From a craft perspective, including the pop culture references is a very concise way to explain a time period or what sort of culture or subculture you are in. Some readers might not get some of the references but those who do, it can feel really special and like an Easter egg, especially if it is an obscure reference. Pop culture is one of the major ways in which we see ourselves and others. In regards to my struggle with identity as brown in a white place or thinking about my body and what it looks like, pop culture had a really direct influence in how I was seeing myself. In the essays about the eating disorder, I write that I grew up in a time when really thin and underweight women, maybe diagnosed or not, were celebrated and idealized. It is really important to not point blame but provide context. My stories would be the same if I didn’t provide those contexts. I was consuming those media and internalizing it. Without those references, it would not be an accurate reflection of my growing up.

My publisher suggested adding photographs from when I was a kid. It was fun to try to find those and put them in. The photographs were an interesting way to support and enhance what I had already written as there are also excerpts of diary entries. Photograph and diary entries feel more personal to me, like a capsule of my experience.

RM: How do you balance your career as a writer, DJ, and educator?

EP: When I first wrote the essays, I was freelancing as a DJ and journalist. My time for writing was a lot easier to fit in as I had a lot more control over my schedule. I was writing this next version of Funeral for Flaca in the beginning of this year, and the balance might look different in the future. My current role as a Director of Youth Programs at Literary Arts is a role that I took on when the pandemic happened in 2020. All of my other event production and DJ-ing jobs naturally fell away during the pandemic. So, I haven’t been really been faced with the struggle to balance everything. I have largely focused on writing in the last year.

But that is a question I come back to, especially as a person with bipolar disorder. I am constantly thinking about balance. I think I need to be really careful about my boundaries and be in touch with myself and my capacity so I can be realistic with what I can take on and also making sure to protect time for myself. It’s really hard not to work sometimes, especially when your interests are things that you monetize. Time for myself can look like I sitting around with my partner and watching Survivor, or going to the park with friends, or going to the river, or taking my dog on a walk.

RM: What do you like to do when you are not writing, DJing, or working?

EP: Normally, I would say that I love to travel and go to music events. In light of Covid, things have changed. It has become my near-daily habit to walk our dog at lunch. I wasn’t a part of that earlier as my partner is a very good dog dad and I was barely home pre-pandemic. I love a body of water so when I can, I go to a hot tub, a river, or lake. My ideal is a slow morning with a good book and coffee. I recently started to read tarot which I am really excited about as I have wanted to do that for a long time.

RM: What advice do you have for writers, especially for writers of color?

EP: First and foremost, please keep writing. I think there’s also a lot of pressure to develop the perfect writing routine and things like that. But I think ultimately it is about writing, and you do that however and whenever you can. For writers of color, we need to hear your stories. Finding a community that is supportive of you and understands your work is super important. During the quarantine, I formed a BIPOC-only writing group. The group has been super healing—to have a space to continually come back to, to talk about writing, to read others’ works, to learn about different writers, to share your work without a huge preamble. Read about authors’ takes on craft, and read other genres. The other thing is to come back to what motivates you. In the last round of edits for Funeral for Flaca, I was distracted by who was going to read this and what the end product was, but you have to learn how to put blinders on so that you can focus on yourself and creating work. I held up a picture of six-year-old me as my motivator. Lastly, whatever you write, you can decide if and when other people read. So, please get something on the page because I want to read it.

You can read more about Emilly here and shop her store here. You can also follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Pingback: RIP Flaca - Future Tense Books