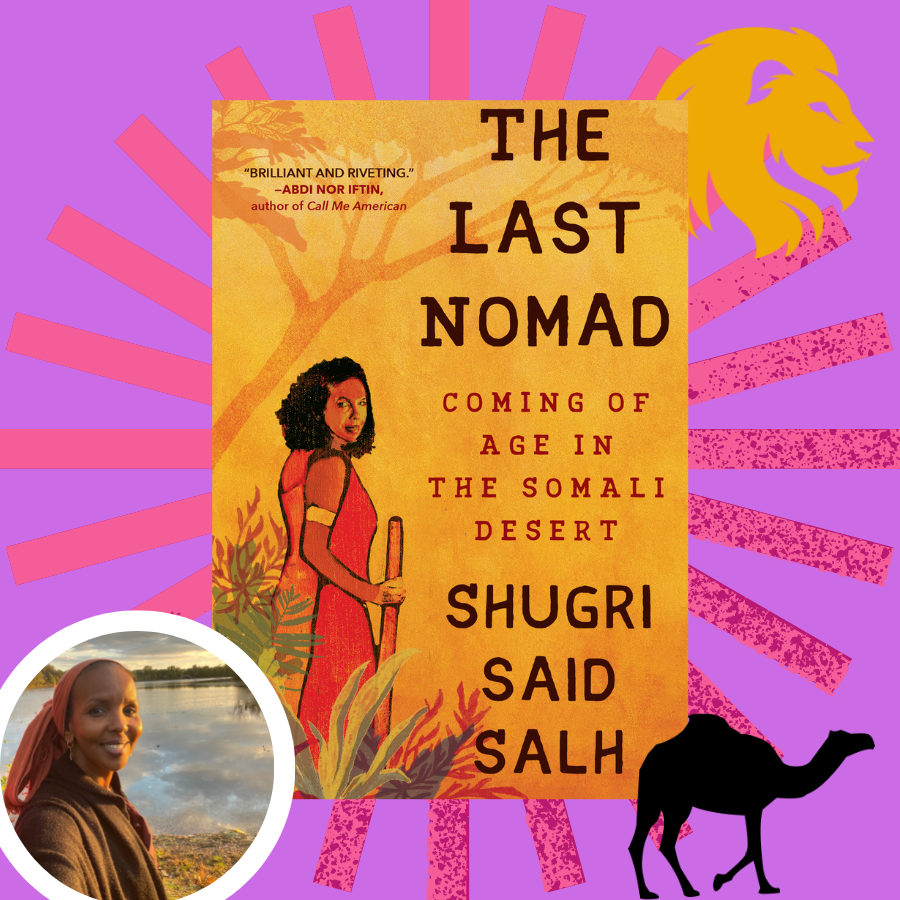

Shugrin Said Salh’s nomadic childhood comes alive in her debut memoir, The Last Nomad: Coming of Age in the Somali Desert. At times touching, at times brutally raw, but always teeming with hope, The Last Nomad is an honest account of Shugri’s love for her war-torn country.

When did it first occur to you to share your story in book form?

I always wanted to tell my story. But it wasn’t until I finished my nursing degree and the kids were no longer latched onto my breast that I took it seriously. That was about seven to eight years ago. I remember I was always sharing little stories here and there, and people would always tell me I had a beautiful way of telling stories.

I come from a long line of oral storytellers to the point where Somalis didn’t have a written language till the early ’70s. We are nomads, and we are one with nature, so we share stories about everything we encounter. After a long day of animal herding, we would come home and share our stories at night as we sat around the fire. Stories about the past, about dangers, about courage, and our fears. Everything I heard as a child was in the form of oral stories, poems, and riddles. These stories had been handed down from generation to generation and were told to us as we kids sat by the fire at night. It was a beautiful way to grow up. That young girl who listened to those stories morphed into this adult who loves, loves, loves telling stories and collecting them as well.

What was it like going from telling stories orally to physically writing them down?

It was a big difference. Humans don’t necessarily speak the way they write, but I really enjoyed telling stories in this form, too. However, it was not without challenges. I wrote, rewrote, and did a never-ending editing process that sometimes left me emotionally drained. At times, I had to say a sentence out loud multiple times in order to capture the essence of what I was trying to compose. In the end, all my efforts were worth it because The Last Nomad resonated with many people. I receive weekly emails and messages from various social media platforms from people telling me how much they enjoyed reading my book or asking me for interviews.

There is an African proverb that says, “When an elder dies, a library is burned.” In Somali culture, we say, “Waarimayside war hakaa haro.” This proverb loosely translates, “You are not going to live forever, so you may as well leave your words behind.” What tickles me is that long after I am gone, my words carrying the wisdom of my ancestors will prevail. And that is beautiful.

How long did it take you to write The Last Nomad?

I think the whole process took about six years. In the beginning, I only focused on writing and getting my story out, and when it reached the level it could be read and understood, I sought agents. It was quite a dedication; every weekend and a few nights during the week, I spent writing and editing. I did this in the span of six years. I became a little obsessed with it. Initially, this memoir was three books long. The editing process was just as long as writing it. It was hard to let go of some stories because I was very attached to many of them.

One story that was left behind and which I wished I kept was the story about the birth of my father. My aabo was one of a pair of twins, but he was born three days later than his twin sister. Every time I share this story with people, it stops them in their tracks. His actual birth story is even crazier. My grandmother went into labor in the middle of the desert, where the closest neighbor was a day’s walk away. After giving birth to my aunt, despite the pain, her labor ceased to progress. It was this time that a lone man traveling came to seek their hospitality. After feeding him and offering him shelter from the wild animals, the man asked what was bothering the family. My grandfather shared with him the difficult labor his wife was having, not expecting the man to know anything about labor. To their surprise, he told them to tie the robe to the top part of the center support post of the hut. The same robe was tied to the fundus of my grandmother’s stomach and wrapped around her stomach in a downward motion. Imagine a rope being wrapped around one side of a water balloon, pushing water content into one side. That same pressure forced my father out of the uterus and into the world. It is amazing to me today. Not only did my grandma not die of infection, but she continued to birth two sets of twins in the same condition.

Did you have any help writing The Last Nomad?

I was lucky enough to have the support of my good friend, Gayla. She was the first friend I made through a mommy and me class when I did not know anyone or even how to drive a car. Gayla and I remained friends over the years. I told Gayla that I wanted to tell a unique life story and how I feel the weight of my ancestors on my shoulder. There was an urgency in my voice that said: If I die today, all my history will finish with me. I felt a rainbow of emotions while writing this book, but Gayla was there with me. There is not a word in this book that she and I didn’t move around or say out loud multiple times to make sure that it captured my tone and thought.

I also shared the early manuscript with a few more friends so they could critique it and guide me. Writing in English, especially when I am under pressure, does not come easy for me. The reality is that I am a nurse, and I don’t have a literary major. I am the kind of person who would score 99% on a chemistry exam, but if a teacher asks me to write an English paper, it will bring me to tears. To overcome this challenge, I just leaned into the storytelling side. I felt rooted within this power; weaving tales is what my ancestors did, and it was and is a nomadic way of life. I watched my family share stories together as they built huts, made yogurt at the height of the rainy season, and reinforced enclosures for their animals. This village-mindedness sustained me through the writing of The Last Nomad, and I suspect it will sustain me for many books to come.

You mentioned in your prologue that you feel like the sole keeper of your family secrets. What is it like having this great weight of responsibility?

It was not like my family had a lot of secrets, but even being honest about the strictness of my father’s discipline made some of my siblings unhappy. We Somalis like to see only in good light those that have passed on. I was not interested in painting anyone in a bad light, but like an archaeologist digging for the truth, I wanted to present my life story as it happened, not as people saw it or wanted it to be.

The weight of that responsibility was huge. When I was writing this book, I actually meditated and asked my ancestors for their permission to tell their stories. They agreed. As I wrote The Last Nomad, the weight of that responsibility urged me on. I did not want to let them down. And when you come from a marginalized community, you want to be fair, accurate, and get it right. But more importantly, I knew if I didn’t do this, then the library of knowledge that not only carried my life’s story but that of all Somalis would have died with me.

In The Last Nomad, the beauty of my country emanated through me. Many people only know about destruction and suffering when it comes to Somalia. My memoir not only captivated both westerners and Somalis alike but captured the beauty of my country.

In the end, I must have done something right because many people called me and told me, “This is one-of-a-kind,” “This is one book they saw as a reflection of themselves and that of their family,” and “Thank you for writing it.” I think this is a gift in itself. It’s truly an honor to be able to give people this precious insight into the life l lived, along with an insight into the lives of many other Somali people.

You are very honest about your experiences. Did you have any fears in sharing so honestly?

I didn’t have fear. In my memoir, you see the humanness of everyone in my story. A good example is my father. He was a hard disciplinarian who, at times, crossed the line with his punishment, but my father was also the man who wanted his daughters to get an education at a time when no one cared to do so. If I made everything look good, I think people would see that I wasn’t being honest with them. If anything, people have said I was really fair and that despite my disagreement with some of the things that happened, I have a lot of love for my culture. I feel very confident, and I think Somalis would not have approved of something if they didn’t like it. Maybe this was a good reason to lean in. People appreciate the honesty of the story.

You mention a lot of last moments that you did not know would be “lasts,” like seeing your mother and grandmother and certain parts of the country. Do you feel a lack of closure from this?

Yes. One thing that bothers me still is that the last time I saw my grandmother, I did not think it would be the last time. This is a huge loss because my grandmother was a wealth of knowledge, and it would have been nice to record her life story. From the moment she was a baby till her death, my ayeeyo lived in the desert. I was only able to capture a fraction of her life story.

The same is true for my beloved Somalis. When I fled from my country, I did think that would be the “last” time, too. There is a deep longing to see my country and visit the land where my mother and grandmother are buried. I think Somalia and I owe each other closure. Like a bird whose nest caught a sudden fire, I fled in terror and never looked back. Every cell in your body demands closure, but the first time the thought of going back to Somalia came to mind, my entire body freaked out. I had these nightmares that felt like I was physically being attacked. It was intrusive and scary. But I was not the kind of person who let fear prevent me from achieving my goals. To trick my body, I slowly introduced the idea in small doses until the nightmares subsided.

Going back to Somalia means facing the trauma a young, teenage me endured as I escaped for my life: the violence, the almost being raped, being stuck in a refugee camp, loss of loved ones. But yearning to see home, and to sift my fingers in Somalia’s soil, to walk the streets I walked when I was a young girl, to look at the sky and the ocean, to stand on a termite mound and feel the air on my skin and my body and just breathe are worth the risk.

Courage and bravery are two main themes in The Last Nomad. You mention that as a young girl, you were naturally unafraid. As you got older, you began to experience more fear. Can you talk about this shift?

I always look at it this way: Courage is not without fear. A lot of things I do in spite of the fear. That brave young girl was mimicking her nomadic grandmother. I am still brave but in a different way. The medical mind in me knows danger now. My life, which was once dispensable as a younger girl, is not anymore. If I lived in Somalia, I might still be okay with facing danger daily, but now I am in a culture where everything is safe.

We make heroes seem like people on a higher frequency, but real heroes are humans like us. I see myself every day being brave and doing things that are right for me. One time I remember, I was walking under a bridge with my children. There was a man who seemed to have some kind of mental and physical issues walking ahead of me. Some teenagers were trying to burn him. I found myself standing with an angry teenager, telling him, “You cannot burn him down.” I will always put myself in danger if it is what is right.

When did you know the book was done?

About the fourth year of working on it, and only after revising and rewriting it many times. If I did not stop then, I would have sunk deeper into the rabbit hole of never finishing my book. Also, my friends were giving me feedback and telling me the book was ready to be looked at by an agent or publisher.

Any final words you would like to share?

I hope the readers will gain an understanding of a culture that is so different from their own. Every time we share stories and learn about each other, we bridge a gap. I know I have been enriched by many books about other cultures, and I hope my book does the same for my readers. I also hope my story will empower others and help them get through hard times as I did. I was born during one of the worst droughts in Somalia, I’ve been bitten by scorpions and snakes, chased by angry warthogs, escaped a civil war, survived a refugee camp, and landed in Canada in the dead of winter, and I am still here! I’m even still functioning! I believe this possibility for resilience lives in all of us.