I recently wrote about the 18th-century French painter Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun for Feminist Book Club’s “Reclaiming the Canon” series, so I was excited to see a new historical novel out about one of Vigée Le Brun’s contemporaries, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard. Susanne Dunlap’s The Portraitist is a novelized account of Labille-Guiard’s career as one of the foremost portraitists of this period. (And, yes, Vigée Le Brun appears in the novel as Labille-Guiard’s primary rival.)

The Portraitist spans a big stretch of time—from 1774-1802, to be precise. This begins with Adélaïde Labille-Guiard’s first steps into the world of professional painting and takes us through the high-stakes frenzy of the French Revolution and beyond. Many of the novel’s chapters begin with a diary-style date (“Paris, August 1774,” begins Chapter One) which keeps things organized. Sometimes entire years pass between chapters, but Dunlap keeps the story primarily in-scene rather than giving into what must have been the temptation of lots of historical summary. As a reader, moving from scene to scene across different time periods felt similar to the experience of being in an art gallery and taking in painting after painting. The years of Adélaïde’s life pass by with lots of drama, but the pacing of the story is always smooth.

Dunlap’s prose is generally straightforward and easy to understand, without compromising the appropriate style and tone of the historical time period. The limited third-person narration is from Adélaïde’s painterly perspective, which means it often remarks on the transformation of lights and colors, showing Adélaïde’s world as a beautiful and exciting one. In the book’s first paragraph, Dunlap writes: “She’d stare hardly blinking for hours, noticing all the subtle variations of hue that, to a skilled eye, gave the sky as much movement and character as a living creature.”

Sometimes the straightforward nature of the narration makes the feminist observations feel a little too simple or obvious, such as when Adélaïde reflects on a female friend’s capability of being “a capable diplomat or civil servant”: “It was sad that such avenues were closed to women.” At the same time, it’s hard to argue with the basic facts of being a high-achieving woman within a strict patriarchy, including the very relatable and direct sentiment: “The fact that men like Gallimard and Nicolas held such power over her, simply because she was a woman, infuriated her.”

Adélaïde is a deeply relatable character in other ways, too, and I recognized my own feelings as an artist in her reflections. When she prepares herself for her first entries to the salon, she considers that she has a year to get paintings ready—”a year to work and worry, to believe one minute she could conquer the world and the next that she deserved to have no more success than a worm in the gutter.” We’ve all been here, right?

While the novel’s plot is full of drama (the French Revolution is no joke!) the most beautiful scenes to me were those centered on art and how art mattered in Adélaïde’s life. I was especially struck by the excitement of the art exhibitions. When Adélaïde exhibits work in her reception salon at The Louvre, the scene of the packed museum is a reminder that this was a time where the only way to see the art was to, well, go and see the art. The vivid salon scene had the energy of a modern-day concert, with all kinds of people coming together to share an experience.

I also found the female teacher/student relationships to be compelling throughout the book. Adélaïde Labille-Guiard was a passionate teacher of young women. Maybe it’s because I’m a teacher, too, but the scenes in which she’s instructing her students, simply getting to know them, and reflecting on her growing community of young women artists were especially touching.

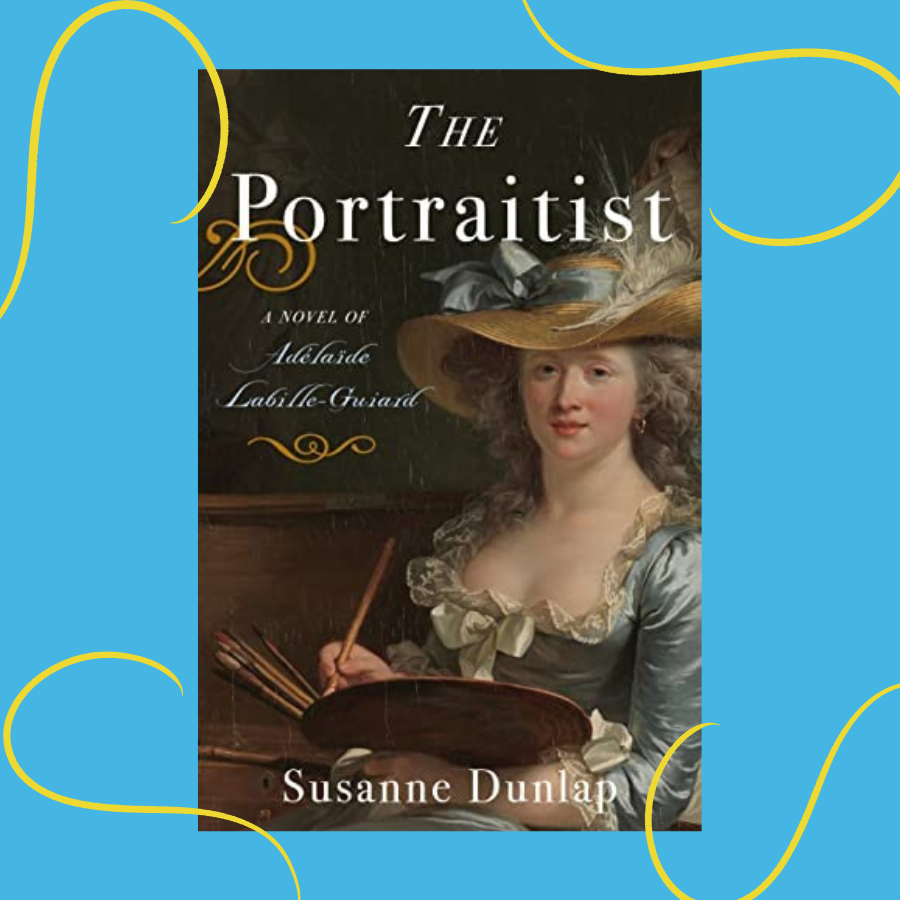

In fact, the cover of the book features a self-portrait that Labille-Guiard painted of herself with two of her students. Here’s the full painting, called “one of the most remarkable images of women’s art education in early modern Europe” over at The Met Museum.

(Can you imagine getting any work done in that dress?!)

While reading The Portraitist, I was reminded of Antonia Angress’s recent novel Sirens & Muses (which we chatted about on the podcast a few months ago) and its exploration of the modern-day art world. In both books, set over 200 years apart, I found myself getting sucked into the drama and intrigue of the art world and its fascinating morality spectrum. Do you make art for art’s sake or art for money’s sake or art for a bit of both? Is there a right answer? How does class play into it? How do people in different places on the spectrum interact? It seems these questions can feel more complicated when you’re a woman, which is a prominent theme in both novels.

As a lover of historical fiction and lady artist history in general, I devoured The Portraitist. Readers who are interested in art history, French history, female friendships (and, yes, fiery rivalries!), feminist underdogs—or who are simply looking for a lovely literary escape—will find inspiration in this novel and empowering fellowship with Adélaïde Labille-Guiard.