This post may include affiliate links, which means we make a small commission on any sales. This commission helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thanks for supporting small, independent media!

The “male gaze” was first named by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey in her 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” The term refers to the heterosexual male perspective that has historically dominated our arts and culture. This is the reason behind frequent film depictions of women as mere sexual objects intended for heterosexual male eyes.

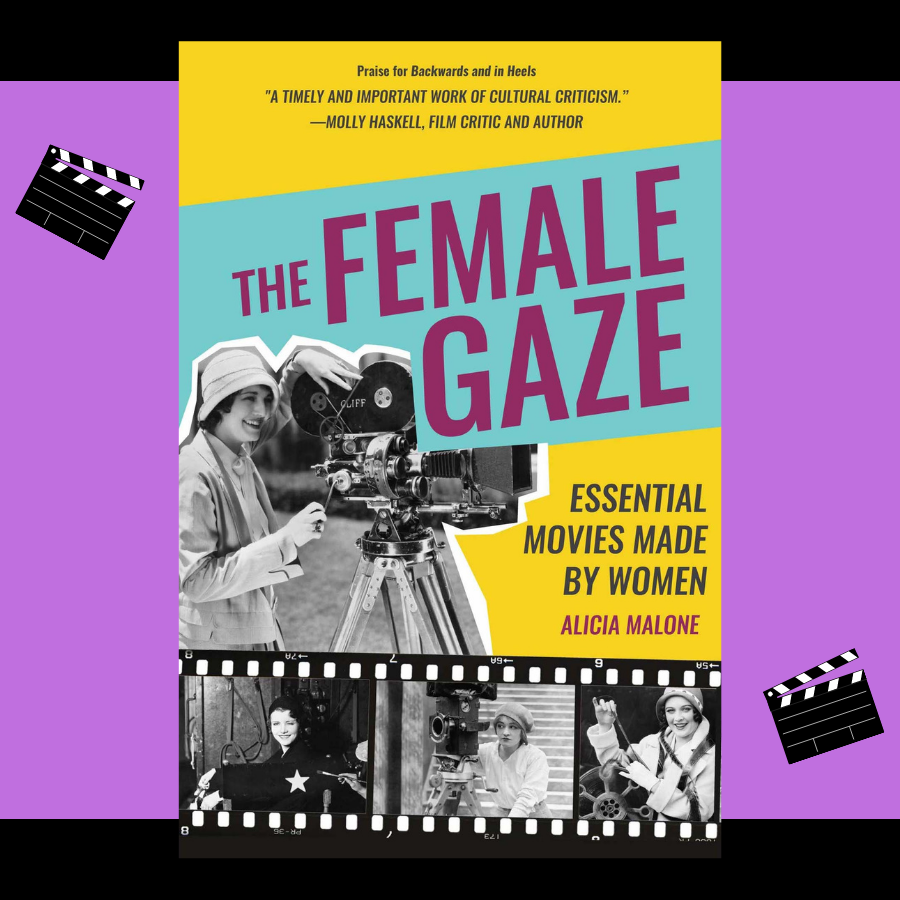

The “female gaze,” alternatively, shows the world through women’s eyes. As Alicia Malone writes in the introduction for The Female Gaze: Essential Movies Made By Women:

“[The female gaze] is a phrase used here to open up a conversation about the experience of seeing film and being seen in film for those who don’t identify with being white, cis, or male.

What happens, for example, when we look at the world from a female point of view? How do women see themselves? How do women see other women? What makes a movie essentially feminine? What can audiences of any gender identification gain by looking at film through a female lens?”

Malone goes on to prove that each of these questions has many possible answers. The Female Gaze: Essential Movies Made By Women is, as its title suggests, first and foremost a list. It contains 29 chapters about 29 different movies directed by women (in chronological order, which I appreciate). Sprinkled throughout the book are short essays about additional movies written by other writers, bringing the total number of films covered to 52. Each chapter contains a summary of the film and its importance, a discussion of the filmmaker’s life (usually including maddening gender barriers), and a succinct statement about how the female gaze works in the film. If you want to watch more movies made by women, you can easily flip this book open to a random page and find a film and a director to start exploring.

I was surprised at how few of the films on Malone’s list I have actually seen. From the book, I learned about new-to-me filmmakers, movies I must see, and fascinating facts about the lives and work of filmmakers I was already familiar with, like Dorothy Arzner, Kathryn Bigelow and Greta Gerwig. (For example: did you know we have Kathryn Bigelow to thank for Keanu Reeves’ action movie career? In case that’s something you’ve been wanting to express gratitude for.)

Malone writes about movies that dig into the experiences of Black women, like Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman (1996) which made Dunye the first Black lesbian to direct a feature film, and Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991) about an African-American family in the early twentieth century, which Malone describes as “a richly crafted tone poem.” She also covers the work of early female filmmakers from Alice Guy-Blaché (who reverses gender roles in her 1906 film The Consequences of Feminism) to Ida Lupino (whose haunting thriller about a serial killer, The Hitch-Hiker, brought her success in 1953).

I was amazed at how many of these movies I hadn’t seen until I hit the early 2000s section of the book. Suddenly I was intimately familiar with each chapter’s film, one after the other: Whale Rider, Real Women Have Curves, Bend it Like Beckham, Thirteen. I was a preteen in the early 2000s and my independent-film-loving mother brought me to the movie theater every Friday night. These movies were so meaningful to me as a young girl figuring out her identity, and it never occurred to me until reading this book that they share that divine female gaze—even if it’s expressed differently in each story. Through these female-led and female-directed films, I found characters to resonate with and stories to be inspired by (actually, Thirteen may have just horrified me but that still counts as influential).

This sudden section of familiarity made me reflect on why I know those movies but not so many of the previous ones. The answer? I saw them in a movie theater. I’ve seen lots of movies made before the 2000s, but, as it turns out, they’re mostly movies made by men (even though women have been directing since the early days of film). It’s almost like female artists are only allowed to exist in the present, and they have a harder time getting admitted into the—dare I say it—canon.

The Female Gaze is an essential supplement to the canon of great films we all more or less know already. The book is easy to read, and each chapter is interesting and succinct. More than being a mere collection of women-directed films, it’s a diverse array of examples of what the female gaze can be and the impact it can have. I highly recommend it as an important resource, but keep in mind that if you really want to dive into any of these filmmakers’ lives and works, this is only the starting point.

I read this book cover to cover, but it’s probably best utilized as a reference book to dip in and out of. That being said, I think the ideal way to use this book (and it’s also suggested by the author) is to pair each chapter with an actual viewing of the film. With 52 films, you have one per week for a year!

Are you up for the task? If so, the #52FilmsByWomen challenge is waiting for you.