This post may include affiliate links, which means we make a small commission on any sales. This commission helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thanks for supporting small, independent media!

The first time I ever lived alone, it was 2016 and I was halfway through my doctorate. It was a stressful time in my life, to be sure (I had spent the previous year watching Breaking Bad on loop as stress relief, if that gives you any indication of how pressured my day-to-day life felt). It was a time in which I relished the luxury of having space completely to myself. And as a serial monogamist still chuckling at discovering that term, it was also my first time being uninvolved in any kind of relationship. I felt free, and a little nervous that I wouldn’t know what to do with myself.

So, reader and lover of women’s history that I am, I picked up Marjorie Hillis’s Live Alone and Like It. Hillis wrote this “classic guide for the single woman” in 1936, and it’s full of delightful chapters like “When a Lady Needs a Friend” and “A Lady and Her Liquor.” It was a fun read, and I felt like Marjorie was my older-single-lady friend supporting me from nearly a century ago at a time when I needed her voice.

But I was reading with a hefty grain of salt, as Marjorie’s problematic POV was not lost on me—namely, the idea that a woman’s single-ness ought to be temporary, and that the sole goal of the woman who is living-alone-and-liking-it is still to get a man. I was aware of this thread throughout the book, but I still emitted a sigh of disappointment at the book’s final lines (spoiler alert!):

This general attitude, not too literally followed, is not a bad one to take through life. If you do so, you will probably not have to live alone and like it.

Excuse me? “Not have to”? I was living alone by choice, thank you! The book left a taste in my mouth that was not conducive to the empowerment I wanted to feel at finally having my own apartment. (Thankfully, I also read All the Single Ladies at this time, and Rebecca Traister’s detailed account of unmarried women’s political power throughout American history blew my mind.)

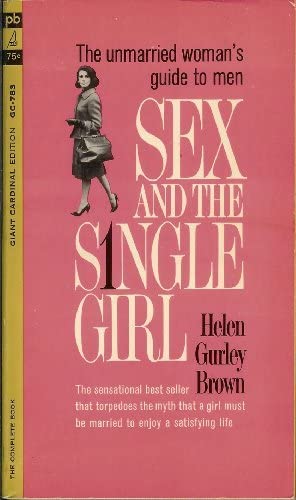

While it didn’t come up for me during my own time of charting new territories of lady-aloneness, Helen Gurley Brown’s Sex and the Single Girl was written with a similar POV nearly three decades after Marjorie Hillis’s guide. Sex and the Single Girl sold two million copies in its first three weeks of being on shelves in 1962, and Brown become the editor of Cosmopolitan magazine soon after her book’s success. The book famously encouraged women to be both financially and sexually independent. This was pretty wild for the time, although Brown was still advocating for the eventual goal of heterosexual marriage. All this single-girl-sex was ultimately supposed to catch a husband.

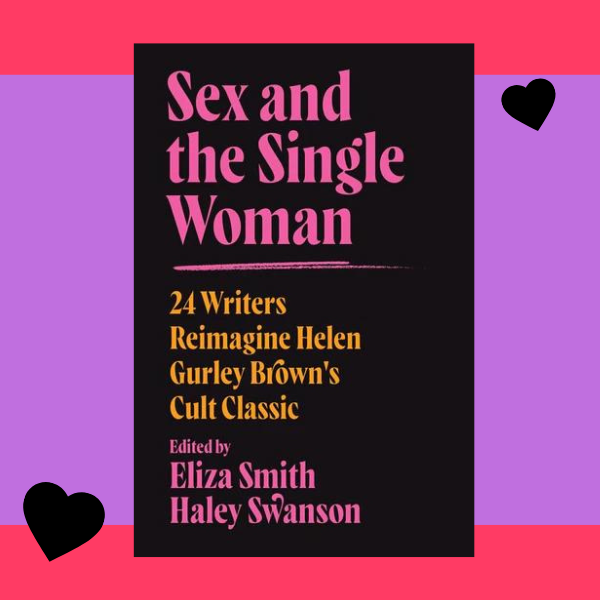

Cue Eliza Smith and Haley Swanson, the feminist writers and friends who co-edited 2022’s Sex and the Single Woman (note the updated title). Smith and Swanson compiled this essay collection to answer their question, “What would a modern Sex and the Single Girl look like?” As it turns out, it looks very different from the 1962 original. Sex and the Single Woman consists of 24 essays by 24 writers, each of whom considers and grapples with a different theme from Helen Gurley Brown’s original manual.

I practically inhaled this book in under 24 hours, which signifies how in need I am of women writers simply engaging in real talk about their life experiences. The essays express the realities of sex and single-womanhood as they are lived today, by individual people in the 2020s (a revolutionary idea, no?). Some of the book’s writers specifically break down and respond to aspects of Brown’s problematic language, which is “at times racist, homophobic, fatphobic, classist, and ableist” as the editors acknowledge in their introduction. (In fact, I often found myself wondering why we were honoring this woman at all, but I suppose this sort of reckoning was part of the book’s goal.) Other essays don’t reference Brown, but focus on a topic of sex-and-singleness that are personal to the writer. While each essay is about a different topic, “loving one’s own body” emerged as a core theme to me.

Many of the essays reference the power of the magazine culture that Helen Gurley Brown helped build as Cosmopolitan‘s editor—and not generally in a positive way. In Shayla Lawson’s essay “The ‘Straight’ Girl,” Lawson writes about reading an advice columnist’s response to the question “Am I gay?” in Seventeen magazine when she was twelve years old. The article said that getting turned on by women doesn’t necessarily mean you’re gay, because girls and women are so accustomed to the male gaze: “So, that was that. I was straight for the next twenty years.”

Other essay highlights include Jennifer Chowdhury’s “In Pursuit of Brown-on-Brown Love,” which details how Chowdhury tried to live her life by Bollywood-love-story rules with plenty of heartwarming humor (“How lucky was I? I hadn’t even started high school and I’d already found my husband!”). Evette Dionne writes poignantly about her experience with IVF and the tremendous social and financial burden it can become—as well as the freedom it can offer. Natalie Lima writes about unplanned pregnancy as a Latina (“Women are made to traverse this world, dodging dicks left and right”) and Kristen Arnett questions consent culture in queer spaces in her essay “Queers Respecting Queers”: “Our (sexist) cultural assumptions that women are less aggressive than men, that they’re ‘safer’ to be around, has meant a total lack of discussion about the problems that occur when boundaries are crossed.”

What I love most about this collection is simply the raw honesty in these essays. This honesty is a refreshing contrast with the tone of works like Sex and the Single Girl and Live Alone and Like It, which both work hard to cultivate a certain tone of “perfect single ladyhood” that is not generally applicable or accessible. The essay writers of Sex and the Single Woman are not afraid to share their true experiences or tell us how they really feel, even when it’s complicated. Melissa Febos dives into masturbation, Laura Bogart shares a heart-breaking memory, and, throughout the book, writers aren’t afraid to say whether they love being alone or if they hate it. As Nichole Perkins writes in her essay “Confessions of a Lonely Feminist”: “Having a partner doesn’t mean I would become an oppressed, helpless damsel succumbing to the patriarchy because I can’t survive on my own.”

Truthful, refreshing, and oftentimes deeply and hilariously relatable, Sex and the Single Woman is the book I wish I’d had back in 2016 when I was living alone for the first time and the world was feeling scarier as we approached the 2016 election. I don’t live alone anymore, and I’m happily partnered up with my fiancé and our beautiful cat. But reading this essay collection reminded me of how good it felt when I had my own space for the first time, when my life was finally open for me to do whatever I wanted with it day after day. Most of all, it reminded me of how important it is to engage honestly with other women—both in the contemporary world and with those throughout history.