This post may include affiliate links, which means we make a small commission on any sales. This commission helps Feminist Book Club pay our contributors, so thanks for supporting small, independent media!

R.F Kuang’s Babel is a captivating and thought-provoking novel that seamlessly blends elements of history, fantasy and dark academia. Set in the 1900s, the story follows the journey of a young Chinese student named Robin Swift, and his introduction to the British empire and subsequent revolution. As he delves deeper into the world of Babel, and Britain at-large, Swift uncovers a secret society and begins to question his identity and belonging at this institution.

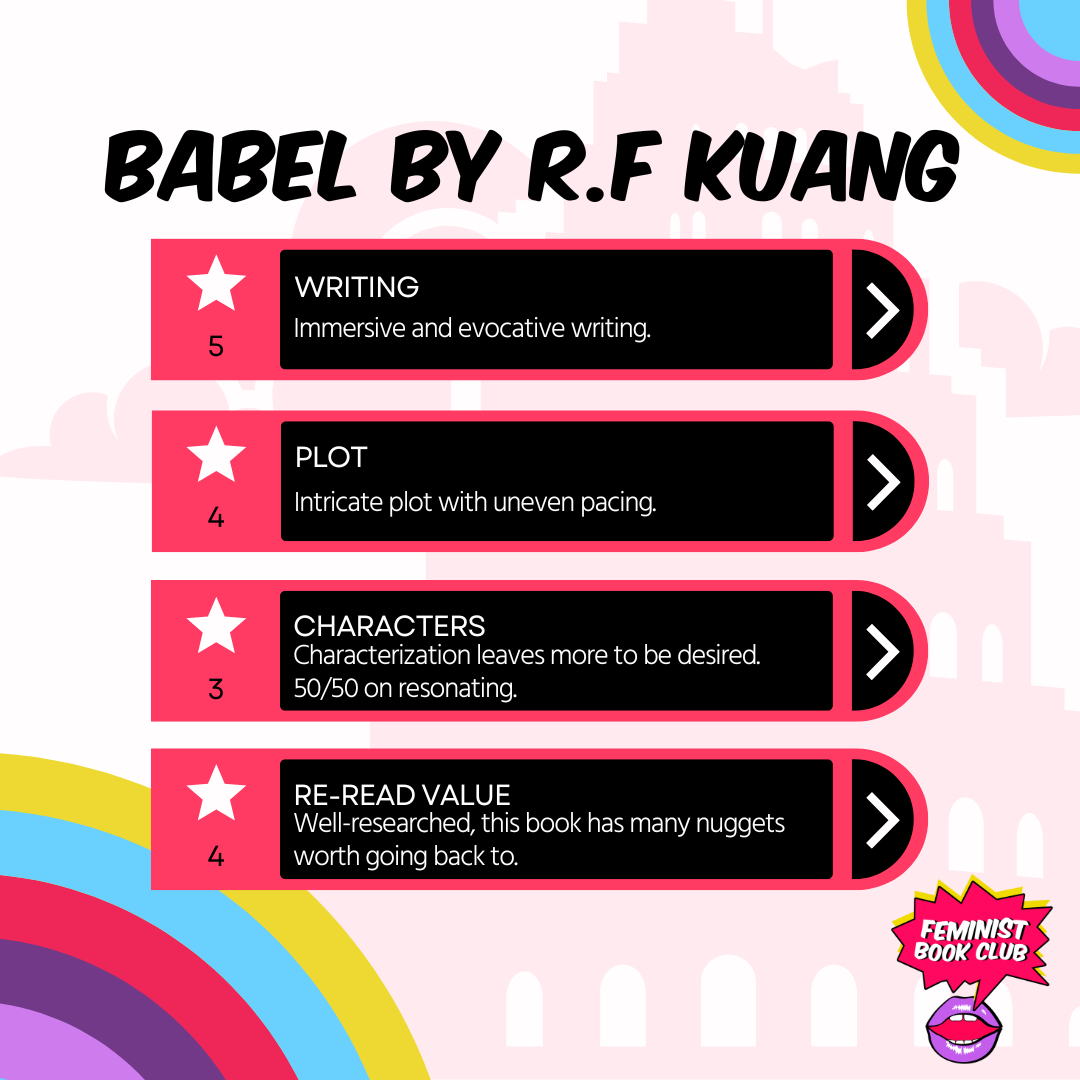

Kuang’s vivid and evocative writing style transports readers into a rich and vibrant world. Her writing is all at once sweeping and personal, lush in its intricate intimacy with its place and time. With well-researched footnotes as flourishes to the main narrative, readers also get insight into a world similar to our own.

Babel revels in its love for academia and the depth of understanding of the powers and systems that impact the day-to-day of common people from colonialism to the interpersonal hierarchies within friend groups. Babel is also straightforward in expressing its themes, and loses nuance that speculative fantasy / fiction readers might be used to.

“Violence was the only thing that brought the colonizer to the table; violence was the only option”

Why is Violence Necessary?

If there’s one thing Babel succeeds at, it’s the careful consideration of the role of violence in a socio-political landscape. On one hand, characters like Griffith push that violence is needed in order to exact impactful and lasting change. Because of the nature of power and capitalism, hurting production destabilizes the system. Those in power would not move unless they had something to lose. Other characters, like Letty and a professor, argue for non-violent reform. Of course, these characters in privileged positions advocate for non-violence. This normative strategy guarantees their own safety within the systems they purport to want to change.

Babel is also an exploration of what it means to be revolutionized, for the less-privileged to observe the injustice around and to actively choose something different no matter the cost. It’s a lesson in sacrifice, how important it can be to causes one believes in.

‘Violence shows them how much we’re willing to give up,’ said Griffin. ‘Violence is the only language they understand, because their system of extraction is inherently violent. Violence shocks the system. And the system cannot survive the shock. You have no idea what you’re capable of, truly. You can’t imagine how the world might shift unless you pull the trigger.’ Griffin pointed at the middle birch. ‘Pull the trigger, kid.’

Though there is no definitive answer to the question of violence, Babel ultimately asserts that violence is necessary for both the oppressor and the oppressed. The powerful wield violence to keep the status quo. The powerless justify their violence as a step towards an imagined, better future. Babel’s argument for violence is especially interesting considering that the casualties of the violence are almost always those lower on the totem pole. I found it fascinating—and bleak— that Kuang, as imaginative as she is, does not envision a revolution without violence inflicted on already oppressed folks.

Babel’s strengths are in its scale. It’s truly an ambitious endeavor to utilize widely known historical events and embellish scenarios into them without losing the realistic touch. It is a more impressive feat to maintain this tone throughout this book. To learn about the history of the British empire is to be enraged. For marginalized communities, reading fiction that validates these feelings can be vindicating.

“He pulled on his English accent like a new coat, adjusted everything he could about himself to make it fit, and, within weeks, wore it with comfort. In weeks, no one was asking him to speak a few words in Chinese for their entertainment. In weeks, no one seemed to remember he was Chinese at all. “

Babel’s lulls are in its pacing and the character-building. Whether or not this is intentional, it does not make for a good reading experience. The uneven pacing contributes to a lack of tension until the ending and dulls the impact of the violence portrayed. There is a minuscule characterization of characters other than the protagonist. This approach to storytelling feels inadequate for its medium.

Though we spend pages with him, Robin is a character that elicits no strong, passionate reaction. Most of his actions are predictable and his predicaments are mild in emotional weight. Ultimately, the characterization lacked substance. Robin suffers from the stoic and academic tone and lacks the compelling, emotional charisma to carry this novel. The single chapters with the supporting cast provided some insight into their perspective, but mostly disrupted the reading process and added no nuance or character development.

With a title like, “Babel, or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution”, perhaps it is an expectation that this novel will take the form of an academic text. Kuang has revealed that her first step in the novel-writing process is thinking of the arguments that she wants her novel to include. And Babel has really good arguments. Colonialism is bad! Translation and languages are cool! Academic institutions are places where we meet the people who support and challenge our thinking but also are physical manifestations of oppressive systems! Elitism takes in a few outsiders and uses them for its gains while taking zero care for their mental and physical health! Sound arguments and good ideas.

It is then, quite sad that the journey with these ideas were not as natural or stimulating. Readers are not trusted to come to these conclusions with their own logic because Kuang overstates these points multiple times and foregoes developing the characters at the heart of this story. As a result, many of these ideas are not fully realized. Though there’s a clarity in prose, Babel is a novel overstuffed with information and lacking in punch.

Despite any and all flaws, Babel is very much worth the read for its relevant musings on race, intersectionality, and language. It allows its readers to reconsider their definition of revolution, face the truths of the British Empire and see how academia is systematically unequal. More importantly, creative liberties set it apart as fiction that dares to reimagine the world and advocate change. As Kuang writes: “History isn’t a premade tapestry that we’ve got to suffer, a closed world with no exit. We can form it. Make it. We just have to choose to make it.”