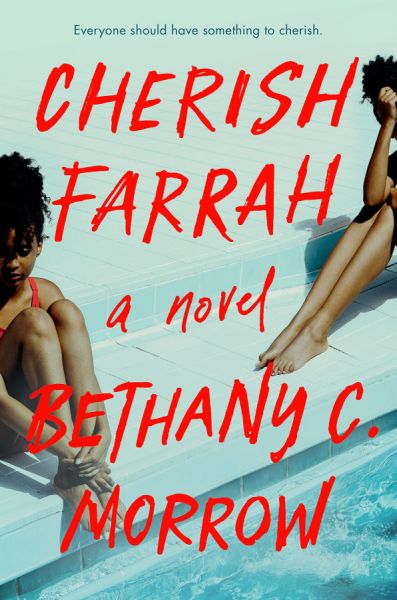

In Cherish Farrah, Bethany C. Morrow has written a novel that embodies social horror, showing societal oppression from a horror lens. Described as Get Out meets My Sister, The Serial Killer, Cherish Farrah delves into the uniquely sinister situation experienced by the only two Black girls in a white country club community as one of them experiences hallucinations no one else sees.

The novel itself speaks to transracial adoption. Pay close attention to the dedication to the novel as well. Morrow keeps her audience on their toes from the very beginning.

In our conversation, Morrow shares what we think Cherish Farrah is about. We also talk about stakes in storytelling, relationships, and what she cherishes.

What is your definition of feminism?

I don’t know if I ever had to come up with one on my own. Unfortunately, it has usually been a matter of recognizing when something is not feminist, and of course, for me as a Black woman, if it doesn’t take an interest in my liberation, in my self-actualization, it’s not feminist.

I think it has to do with action, as well as an ethos. If you truly believe in something such as equity, such as liberation, such as freedom, any of it compels action. As we live in a patriarchal society, it has to be constantly at work to dismantle the oppressive structures directed at women, femmes, basically non-male members of our society.

What is Cherish Farrah about?

Without spoiling it, I can talk about what we think it is about. Cherish Farrah is about the only two Black girls in this very white country club community, one of whom is raised by Black parents and one of whom is raised by her adoptive white parents, The Whitmans. Because they are the only two Black girls, they have a close relationship. They are very dependent on each other. I have heard it described as a “cruel intimacy.” They are constantly edifying and confirming it as the most important thing in their lives in sometimes troubling ways. Farrah is not your typical 17-year-old. She, in her own words, says she is cosplaying a teenager. We see that she has a budding psychopathy. She is extremely cunning; she is extremely manipulative. She is unsettled by her loss of control because her family is going through foreclosure. Her life is being upended.

How do you write your stakes?

The most important thing — other than language because I adore language and rhythm and pentameter — is talking about world-building. World and character are on a feedback loop for me. Everything you learn about the character solidifies something about the world. What happens in the world should be formational to the character. As long as I know the character and the world well, it should be easy to know what someone is expecting to be the stakes.

As a former student of sociology, you realize that our imaginations are not created in a vacuum. It is possible to write to the audience that is not true to the world. It is important to me that the stakes are to the character, not necessarily to the reader. I know what Farrah wants. I know exactly what she believes. I know how to interrupt it, how to destabilize her.

There are poignant quotes about innocence pertaining to Black girls. What did you want to say about the differences in how Black girls move in the world?

I never over-explain because I don’t believe people who pretend they don’t know. Anything I want to say is pretty explicitly stated. While white girls are treated to an infantilization and a mainstay in white supremacist fantasies, the opposite is true for Black girls. We are stand-in adults from a very young age.

I worked with a school in Seattle, Washington. Virtually, I had a group of Black girls that I met with on a weekly basis for the last academic year. I did this because when we talk about the dropout rate, we are actually only talking about Black boys. The statistics for Black girls are worse but do not get the same attention because it is not of value. They drop out because they have to help at home. Why would that have to be acceptable? They are children. Black girls are never seen as innocent children. If a grown man pays attention to a child, she is fast. There is an assumption that she is intentionally creating this. It is so insidious and prevalent in so many Black communities, particularly the Black church. Farrah’s parents know the adultification. The Whitmans get so much credit because they are raising their child like a white girl. They are raising her with this privilege that is not meant for her, that won’t make sense anywhere outside of this bubble they have created because she is unaware and unprepared for reality.

Farrah speaks of her parents often in third person. What did you want to say about relationships and appearances? What do you want readers to take away with social horror?

The thing about Farrah and what Brianne Whitman cannot wrap her mind around is that Farrah is Farrah. You have to see and acknowledge her as an individual to see what she is dealing with in a way that infantilizing and demonizing do not allow you to do. If you can’t see the individual personalities, the humanity of Black girls, you are going to miss that you have a psychopath in your midst.

Farrah has lucid hallucinations. She is always scheming. The fact that no one can see it is a statement on how we don’t give Black girls our attention, the benefit of attention and actually seeing them. You wanna know when you have a Farrah in your life.

What I want people to take away from the social horror is you don’t get to participate in it if you don’t realize the society you live in. That’s why I love the genre so much. It tells on the reader. You can’t enjoy this if you don’t acknowledge the inequities of the real world that would create these personalities. For Farrah, it is abnormal for a Black child to be afforded all of these things. Anyone who reads this book and is uncomfortable, you are telling on yourself.

Why did you name it Cherish Farrah?

You are used to the title changing once the book is acquired. Everyone said, “No, you have to keep this title.” Because you think you know what it means. Then it becomes a command, a warning. It is Cherish’s name, but the Whitmans also named her. Very much it is a warning. I don’t believe you can cherish something you don’t know, that you don’t understand, that you haven’t witnessed. To cherish Farrah, you would have to know her. It is a warning to learn to cherish us individually. I chose that part of the poem for the dedication because I realized that someone is going to terrorize you back. [Editor’s Note: The line, “Beware the day they change their minds” appears in the introduction to Cherish Farrah.]

What do you cherish?

Black girls. You can look at anything I write, across any category, across any genre, but people know where my heart is because there is the throughline. No matter how terrifying Farrah turns out to be, I want her to have a happy ending, so I gave her one.

Where would you like us to buy Cherish Farrah from?

Loyalty Bookstores, in D.C. and Maryland, which is Black-owned, and Cafe con Libros, which is in Brooklyn and is also Black-owned.

Thank you, Bethany C. Morrow for speaking with us at Feminist Book Club! You can follow her on her website as well as on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.